By Steven Boothe, Head of Investment-Grade Fixed Income at T. Rowe Price

Diminished price discovery, flawed sampling methodologies, elevated transaction costs, an inability for passive investors to participate in new issues, and poor index construction. We agree with many of these. But there are other deeper‑rooted issues that have caused fixed income market structure to deteriorate, raising the risk of elevated volatility. In this paper, we examine some of these issues.

The limitations of passive: questionable assumptions

The hypothetical passive investor holds a portfolio that contains every single security in the market, weighted by their market value. The return to this investor would be the market value-weighted return of each security in the market. In theory, this passive investor is endowed with a portfolio that incurs zero trading costs.

However, the theoretical passive investor is just that—an academic construct. In practice, we find that the underlying assumptions of a passive investor are immediately violated. For instance, the endowment assumption is violated daily because of varying flows into and out of the portfolio, necessitating trades.

The zero trading costs assumption also falls short over the long run. For instance, consider the coupon and maturity payments generated by a fixed income portfolio. These produce meaningful amounts of cash that the passive manager must reinvest into new bonds that enter the index in order to track the market.

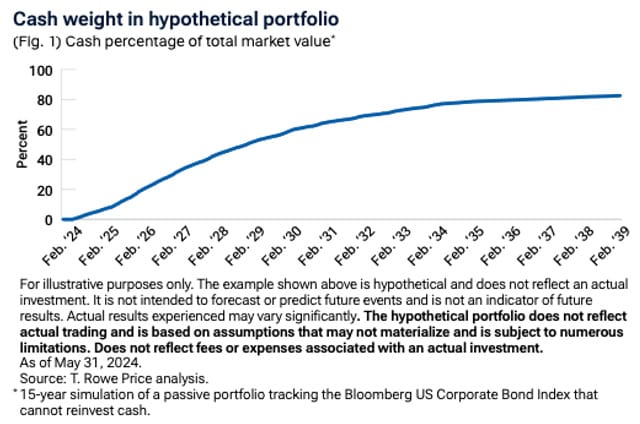

The analysis in Figure 1 shows what would happen to a passive portfolio tracking the Bloomberg US Corporate Bond Index if the manager cannot make transactions to reinvest cash. The cash weight in the portfolio rises to over 80% during a 15-year simulation. Indeed, after around two years, cash has comfortably increased to more than 20% of the static portfolio. Every time a manager is forced to transact, costs are incurred, violating the assumption.

The reality of inelastic markets adds to volatility risk

Each of these examples is important as both involve passive managers being forced into the market to transact— either because of varying inflows and outflows or through a need to reinvest cash. This forced trading, irrespective of fundamentals or valuations, makes passive managers a very simple algorithm. When presented with cash, the passive manager will mechanically invest until all cash has been deployed. Alternatively, when presented with an outflow request, the passive manager will sell a vertical slice of the portfolio—pieces of all holdings in proportion to their index weightings—irrespective of valuations.

Also read: In The Spotlight – FLOT, QPON and SUBD

Under standard asset-pricing models, these flows would have a very limited impact on the market. Put another way, the market was classically thought to be elastic—not reacting significantly to buying and selling pressure. In fact, classic asset‑pricing models1 estimate that the elastic multiplier is somewhere between 0.05 and 0.1 for the U.S. stock market, for example. (With a multiplier of 0.05, a buyer of 10% of the stock market will lead to just a 0.5% increase in prices.)

However, recent academic work hypothesizes that the market is significantly less elastic than previously believed. In a seminal paper, Xavier Gabaix and Ralph introduced “The Inelastic Markets Hypothesis,” in which they proposed that the multiplier could be as high as 5. In that world, a buyer of 10% of the stock market would cause prices to rise by 50%, far more than the 0.5% in classic models.

Why are markets so inelastic? In another key paper, Haddad et al. observed that as passive funds have taken share from active managers, the elasticity of markets has declined. Classically, as more investors become passive, the remaining active investors should trade more aggressively to take advantage of fewer competitors. However, what Haddad et al. found was that the remaining active managers do not respond by enough—and that the growth in passive has led to markets becoming 15% more inelastic over the past 20 years.

Although most of the academic work related to market elasticity has focused on the equity market, we see many parallels to the corporate bond market. For instance, the rise of passive investing, the increasing presence of mandate‑constrained investors such as life insurance companies, and the general lack of liquidity relative to the stock market leads us to believe that many of these hypotheses extend to corporate bonds.

Implications for investors: Inelasticity cuts in both directions

While this inelasticity has helped recent inflows to passively managed funds drive prices higher, a reversal of flows to passive products—perhaps driven by outflows from retirees or a period of outperformance by active managers—would have the opposite effect. This means that inelastic markets are exposing investors to more extreme parts of the return distribution, or the “tails.” This calls for strategies that can provide payoffs when returns are in these “fatter” tails.

Another key implication is that market‑based pricing should not be relied upon as a gauge of underlying economic conditions. To illustrate, see our recently published papers on how the market‑disciplining power of proposed long-term bank debt is being seriously called into question. If flows into passive corporate bond products remain strong, credit spreads will continue to tighten and the so-called market disciplining power of bondholders on bank management teams may be compromised.

Finally, these analyses provide a powerful framework to examine the implications of flow-based activities in markets. For instance, debt (or equity) buybacks exert a powerful upward effect on asset prices, and quantitative easing, when extended to corporate bond and equity markets, can provide powerful tailwinds to asset prices in the near term. But the unwind can expose markets to violent moves downward. Active managers can apply this framework to position their portfolios to help cushion these downturns, while passive portfolio managers have to endure the brunt of the selling.