Last month, there was a moment that analysts and financial market participants had been hoping for some time. Like kids waiting for Christmas morning, market participants cheered when US inflation finally started to ease, and boosted hopes that inflation, at least in the US, had peaked. Naturally, global equities rallied, bond yields have fallen and the US dollar is down from its highs.

However, many Fed officials have been cautious about reading too much into the data release. And understandably so. After all, one data point does not make a trend. There are also the ghosts of inflation past, where a retreat in inflation did not prove to be long lasting.

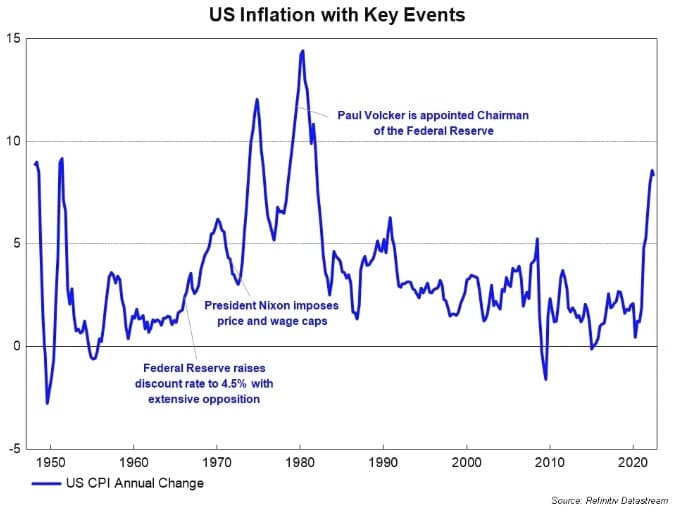

Comparisons have been made between the current inflation episode with the 70s “Great Inflation”. In particular, there were instances throughout the late 60s and 70s when inflation receded only to rise again. A sustained fall in inflation did not eventuate until the 1980s when Fed Chair Volcker was at the helm of the US Federal Reserve. Volcker’s tough stance on inflation has been credited as a factor in bringing down inflation and set the groundwork for inflation targeting that characterizes modern central banking today.

One key lesson from the 70s period was the importance of establishing credibility by the central bank and its role in anchoring inflation expectations. However, there were a variety of other factors that led to the persistently high inflation of that period. Here are a few other reasons:

1) Overconfidence among economists in assessing the state of the economy:

Historians and research papers point to an interesting obsession toward the natural rate of employment – that is, the lowest possible unemployment rate that can be achieved without generating inflation. There was an assumption among policymakers that the unemployment rate consistent with full employment was at 4%, and one historical paper suggested that some thought it could be as low as 3%. Because the unemployment rate was above these estimates, many policymakers argued against tighter monetary policy in the mid-60s even though inflation was edging higher. The goal of achieving full employment also seemed to be of greater importance than price stability.

Also read: The Australian Economy – Back On Track In 2023?

2) Reliance on price controls and wage caps to control inflation, which did not work over the long-term:

A temporary freeze on all prices and wages throughout the United States was announced by President Nixon in 1971, in an attempt to limit inflation. Inflation did end up easing from an annual rate of 4.4% in August 1971, when the policy was announced, to an annual rate of 2.9%, a year later. However, any student of economics would know that the price controls created all sorts of market distortions, and shortages across the economy. Images within media at the time included long queues to fill up cars with gas and farmers drowning chickens. Any student of economics would also know that price controls prevent the price signals to producers and consumers to adjust supply and demand, respectively, and which help to ultimately bring down inflation. Inflation eventually skyrocketed to over 12% in 1974.

However, the most dangerous aspect to this policy was that there were hopes that it alone could address inflation. Consequently, it may have undermined efforts by the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary policy sufficiently, and it may have also limited the incentive for the government to restrain spending.

Full independence of the central bank was also in question. An infamous showdown occurred in 1965 between then Fed Chair Martin and President Johnson after the Fed Board of Governors just raised the discount rate. And accounts of recordings of President Nixon’s conversations highlighted how Nixon repeatedly sought to influence Fed Chair Burns throughout much of the 70s to keep monetary policy as easy as possible.

Ultimately, tighter monetary policy from the US Federal Reserve was in not in step with fiscal policy objectives at the time. Which brings us to our third point:

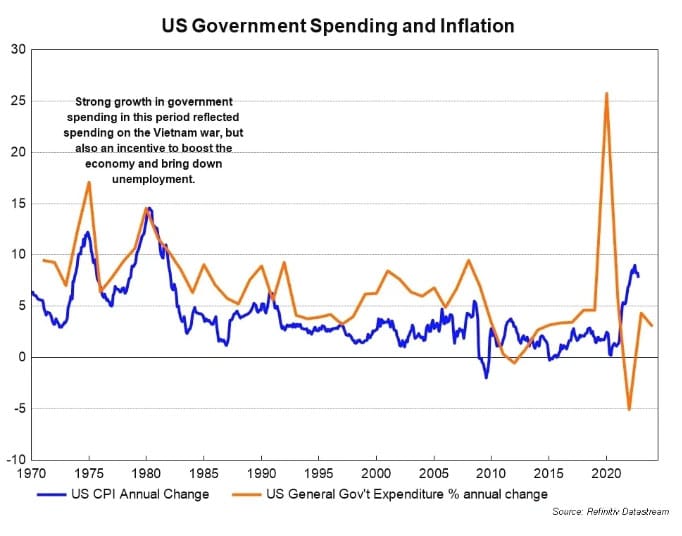

3) Government spending also added to inflationary pressures:

Both the Johnson and Nixon administrations over that period were in favour of bringing down the unemployment rate and to support the economy. This mentality, along with spending on the Vietnam war led to high deficits and rapid growth in government spending. The appropriate monetary policy settings to offset fiscal spending at the time would have had to push a lot harder against this tide.

Lessons for Today

With inflation near 30-year highs in most developed economies, we can understand why a tough stance by central bankers has been adopted. However, from what happened in the 70s, we can gain some confidence today that history won’t be repeated.

We have some better understanding of inflation, its causes and how to tackle it. We have recognised the importance of central banks having independence from governments in regards to their decisions surrounding monetary policy. Moreover, governments are encouraged by the public to align fiscal policy with the inflation objectives of central banks.

The market reaction to the UK mini-budget highlights there is greater public awareness keeping governments accountable in their impact to the inflation outlook. That being said, there have been some worrying developments within Europe. There was strong support within media for former UK PM Liz Truss’s energy subsidies – note that Nixon’s price and wage caps were wildly popular at the time. Meanwhile, Germany has implemented price caps on energy over 2023. These have been marketed at supporting low-income households and businesses, but it is essentially a stimulus measure and has longer-term inflationary consequences, provided market prices stay high.

The temptation remains high for price caps, as they can bring down inflation temporarily and be seen as taking action from sympathetic politicians by the public, although the end result is that the policy will likely exacerbate inflationary pressures down the track.

Another big lesson is for economists and central bankers and to not place too much faith in what forecasts and models are telling us. Events would have turned out significantly different if there were greater doubt about what was the true level of the unemployment rate at full employment. There is a much wider range of data and more sophisticated methods to analyse exactly what is happening in the economy today. That being said, today there is a fascination around a different theoretical economic construct. Rather than the natural unemployment rate, the focus for economists and central bank policymakers has been the neutral interest rate. This is the level of interest rates which are neither restrictive nor stimulatory.

Encouragingly, economists don’t pretend to know exactly what the neutral interest rate is, and there is greater attention to what data is actually telling us. Now that interest rates are approaching what central bankers think is close to being restrictive there is merit in taking a moment to assess economic conditions after such significant moves in interest rate settings.

The stronger resolve and ability for central banks to act on inflation sets this period apart from the inflationary period of the 1960s and 70s. A softening global demand outlook suggests inflation should be on its way down. However, should inflation prove stickier and persist longer, central bankers around the world have indicated there is no hesitation in tightening monetary policy further, a key lesson from the past. In the words of Mark Twain, “history never repeats, but it often rhymes”.

This article first appeared here.