With surging inflation amid record-low unemployment over the past 18 months, discussions about “secular stagnation” have receded into the background.

However, today’s high inflation stems from severe supply-side shocks (war, sanctions) and interruptions to supply chains (due to the pandemic), coupled with large but temporary increases in spending (fiscal stimulus, pent-up demand as pandemic lockdowns ended).

Stephen Dover, Chief Market Strategist, at the Franklin Templeton Investment Institute notes: “Given these factors, the focus on inflation, while justified given its acceleration and breadth, may nevertheless distract attention from longer-term drivers of growth, inflation, and interest rates. In short, secular stagnation may still be the driving force impacting long-run outcomes for asset values.”

Secular stagnation is a prolonged period of chronic underinvestment in productive enterprises (investment in plant, equipment, and new technologies) relative to the amount of savings in the economy. Secular stagnation leads to both a lower trend rate of growth as the “supply side” grows more slowly and to a deficiency of demand as excess savings imply a shortfall of spending in the economy.

As a result, the economy tends to produce underemployment, low inflation, and very low real and nominal interest rates, says Dover.

Also read: Three Floating Rate Bond ETFs – FLOT, QPON, SUBD

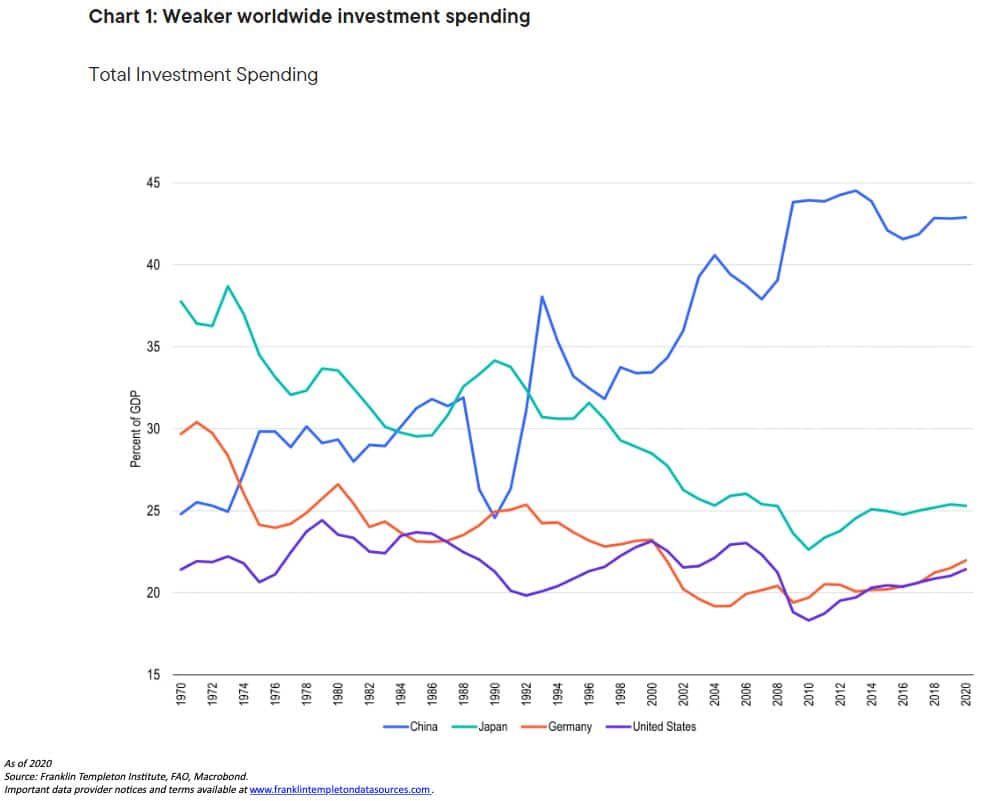

“If we look more closely, we can see troublesome signs that secular stagnation remains a credible description of broad economic trends. For example (Chart 1), gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP)—a measure of total investment spending in the economy—has been declining in advanced economies (i.e., United States, Germany, and Japan) since the 1970s and, despite some recovery over the past decade, remains below average investment rates seen in the 1980s, 1990s or early 2000s.

“Even in China—the world champion of capital expenditures over the past quarter century—rates of investment peaked nearly a decade ago and have been gradually receding ever since. The world cannot be characterised as experiencing a boom in capital expenditures. Rather, large swathes of the global economy are seeing evidence of weak capital formation, a story that may also be unfolding in China,” notes Dover.

He further notes:

Why is investment spending relatively weak?

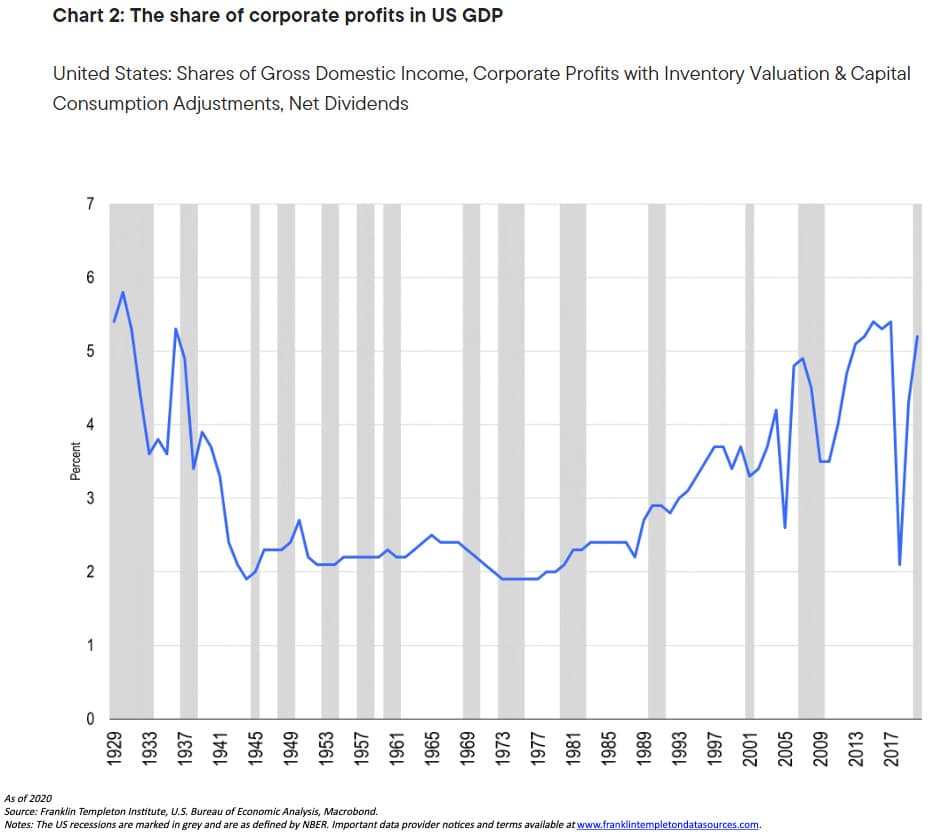

More tepid capital expenditures strike many as an oddity. After all, we live in a world of breathtaking invention and innovation. Moreover, in many advanced economies (above all in the United States), corporate profitability in the 21st century has attained levels (e.g., profit share in GDP) never previously sustained in the post-WWII period. Surely, innovation and profits should spur capital spending?

Perhaps not. Much of the innovation that dazzles us today is either directed at consumption (think video streaming services, social media, gaming, or smartphone applications), speculative purposes (e.g., cryptocurrencies) or is not fundamentally improving the efficiency of our daily activities (alternative energy, battery-powered cars). Those inventions may give us pleasure, occupy our minds, race our hearts or make us feel better about the planet, but they are not enabling the masses to produce more with less—the essence of productive investment.

Moreover, high profits may partly reflect increased industry concentration, not more valuable goods and services. Technology, among other things, allows firms in information technology, consumer discretionary and other key sectors to create monopolies or oligopolies defended by high barriers to entry. Rather than spur new investment, the presence of market power deters it.

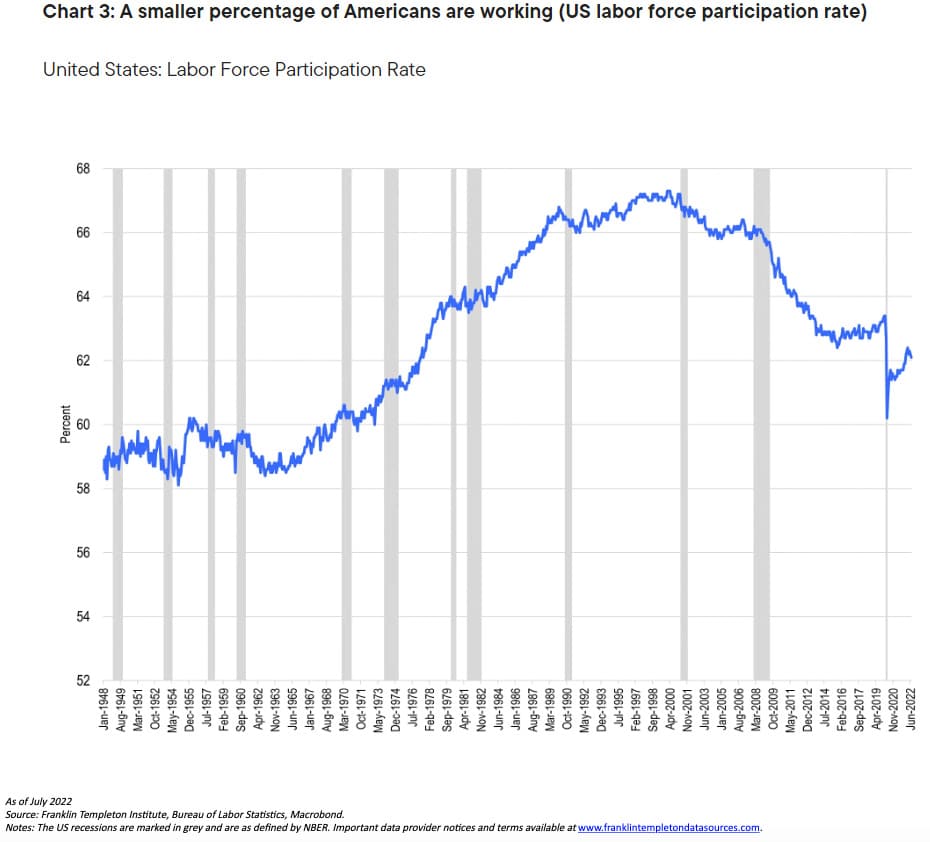

Moreover, as Alvin Hansen, who coined the term secular stagnation in the late 1930s noted,1 low rates of business investment spending relative to savings can be driven by demographics (stagnating or declining population growth, peaking labor force participation), income inequality (leading to high savings by the very wealthy and constrained demand by those living at the margins), and high levels of indebtedness (which constrain the ability and willingness to borrow and spend).

Secular stagnation could also return for another reason—the need to rein in and ultimately reduce mountains of public debt created during the pandemic, which implies higher taxes and fewer government services in the coming decade. This ultimately leads to a further drag on total spending in the economy.

What are the implications for growth?

If secular stagnation remains the key long-term narrative for the world economy, global growth will slow to a weaker trend rate of growth. As we have noted, the key inputs to trend growth—labor force growth, the rate of business investment, the pace of technological change—all appear challenged. In the United States, for example, labor force growth has been decelerating over the past few decades as big jumps in female participation and boomer generation cohorts stagnate or reverse. Capital expenditures and innovation, as noted above, are not taking up the slack.

In addition, the slowing pace and possible reversal of globalization are likely to harm business investment spending and growth. Despite commentary to the contrary, globalization in the postwar era made economies more efficient and more productive. Trade is positive sum. Now, as supply chains are trimmed and, in some cases, brought back onshore, the impact on global economic activity is negative. The same is true for immigration. As borders are sealed and worker mobility is constrained, economic activity is damaged over time.

What are the implications for monetary policy?

Secular stagnation implies a very low, perhaps even negative, equilibrium real interest rate. That is because to generate full employment, borrowing costs must be sufficiently low to induce business investment that might not otherwise take place because of weak demographics, spluttering innovation or general perceptions of a diminished future.

Although the Federal Reserve and other central banks today are now hiking interest rates to lower current high rates of inflation, they cannot completely ignore the implications of very low long-run equilibrium interest rates. Slowing demand and curbing spiking inflation today are necessary, but overdoing things could be very damaging. The interest rate required to slow growth and lower inflation could be much lower than a federal funds rate of 3.5%-4.0%, which is increasingly the consensus view. Hiking rates to those levels could be overkill, in my view.

What are the implications for capital markets?

Secular stagnation, if it persists, presents investors with significant challenges, many of them already familiar from the past decade. After their recent jump, interest rates on risk-free assets, such as US Treasuries, will likely revert to much lower levels. That will recreate challenges for income-oriented investors.

Weak GDP growth implies that profits growth will also be pedestrian. Moreover, if profit share in GDP remains elevated political pressures stemming from income and wealth inequality will only increase.

Growth styles which favor the relatively few companies that can sustain high earnings over time (including via monopoly or oligopoly power) appear likely once again to outperform value and cyclical styles that are offer fewer profit opportunities in a world of secular stagnation.

Finally, low interest rates may again spur unproductive speculation in the customary places, including property markets or cryptocurrencies, or in new ones devised to capture the allure of high returns.

This conclusion that secular stagnation may lead to a focus on longer-duration assets may be surprising to some, but highlights the constant push and pull between economic forces and capital markets.

- Source: The American Economic Review, “Economic Progress and Declining Population Growth,” March, 1939. Information Administration (EIA), December 2020.