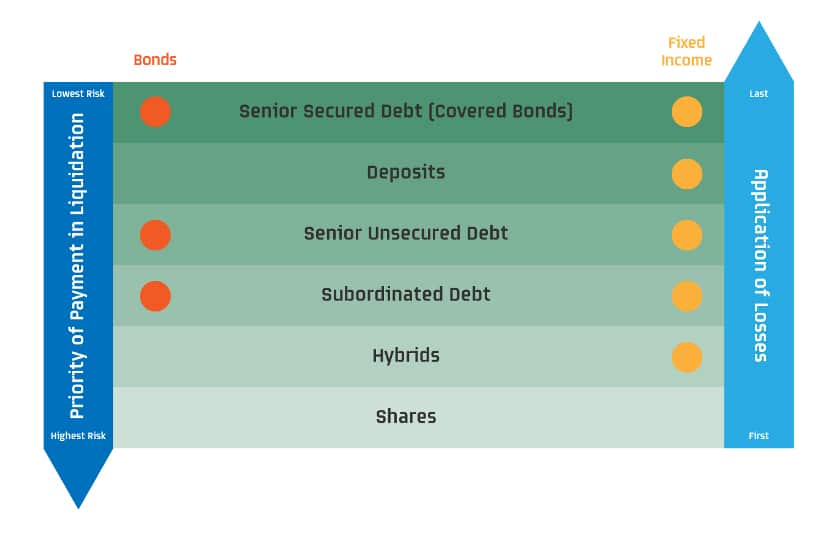

Every company has a capital structure. It tells liquidators the priority of payments in a wind up or liquidation scenario.

It is important to understand that bonds can sit in three different positions in the structure and each position has a consequence for risk and reward. The lowest risk position is the highest on the chart. Investors that hold senior secured bonds must be paid before other bondholders and the bonds are secured over certain assets.

In the case of a property company, it might be a building, while bank senior secured bonds, known as covered bonds, may be secured by up to 8% of the bank’s mortgage loan pool. In the event of default, proceeds from sale of the security must be used to repay the secured bondholders before any other debt holders receive funds. If for some reason the sale proceeds do not repay the debt, investors have further recourse over the company or banks’ remaining assets.

Being very low risk, these investments have very low returns.

Senior unsecured debt (senior bonds) are the most commonly issued corporate bond and do not have any defined security. Rather the company guarantees to repay interest and principal as set out in the information memorandum. Failure to make the payments, can be deemed a ‘default’ and there are serious legal ramifications.

Subordinated debt (sub debt) is junior in the capital structure and all senior debt must be repaid before these investors receive any capital in a wind up. These bonds have additional risks, including the possibility of a longer than expected term to maturity. A longer term means greater uncertainty and investors need to be paid a margin above the higher ranked senior debt to compensate.

For example, financial institution subordinated debt is typically issued as 10-year debt with a non-call five year period, expressed as 10YNC5. Investors would expect repayment after five years (at the institution and APRA’s discretion) but the company is not legally obliged to repay for 10 years. There can be additional call prices above or below par.

Financial institution subordinated debt can be used to ‘bail out’ the institution if it gets into difficulty. In the worst case scenario, the bonds can be converted to equity (shares) to ensure the survivability of the bank.

Hybrids sit below sub debt but above equity in the capital structure. They are complex investments that historically acted more like a bond but over time have evolved to become more equity-like. Principally, they are ‘loss absorbing’ instruments that convert to equity on breach of a capital trigger or determination of non-viability by APRA. While they are often referred to as convertible bonds, they are perpetual instruments and thus do not satisfy many institutional investor mandates.

Shares are always the lowest level in the capital structure. The company has no obligation to pay a dividend or return capital. There is no maturity date. Investors at this level expect the highest returns but they take on the highest risk. In a wind up or liquidation, the capital structure works in reverse. Losses are applied from the lowest level up, share holders are in the first loss position.