At first glance the proposed new changes to small business insolvency and liquidation seem positive, but who lends to the businesses and how do they raise funding? It soon becomes apparent that the changes will impact more than just small businesses.

With modest fanfare, the government announced changes to the small business insolvency and liquidation regime. On September 24th, Treasurer Frydenberg informed those of us listening that from 1st January 2021, legislation will introduce a “debtor in possession” (DIP) model and a “simplified liquidation pathway” to winding-up and liquidation procedures. Already this sounds complicated. In fairness though, this initiative aims to reduce complexity and speed up the painful part for small business owners, creditors and employees. For the nerds out there, the details can be found here.

Why should investors in the bond and fixed income markets care? After all, the borrowers using the debt capital markets are large and this applies to the very small. Well, investors should care in the same way that ripples from a pebble thrown into a pond eventually reach the shore as waves. The new provisions apply to businesses with less than $1m in liabilities, who would rarely (never?) use the bond markets for funding.

Agreed, but by number, this change affects the vast majority of Australian businesses, if not by market value. Government figures point to 76% of all businesses entering external administration in 2018/19 owing less than $1m to creditors. So, chances are, if a business is going under, it’s captured by these changes.

At this point, lightbulbs should start coming on, because which entities are in turn lending to these small businesses? Banks, building societies, and a wide range of non-bank financiers. And those players certainly do access their funding from the wholesale capital markets, from investors like you.

[Also read: Check Yourself Before You Wreck Yourself]

In short, the changes will mean that small business owners will retain some control while going through a restructuring or work-out process and negotiating with creditors.

Previously, an external administrator would be appointed and the business owner would cede control of that process, despite arguably knowing more about the business than anybody else. A Small Business Restructuring Practitioner (SBRP) must now be appointed by a company’s board (for a fixed fee), and together they have 20 business days to formulate a restructuring plan. Creditors then have 15 business days to vote on the plan, with a vote of more than 50% of (non-related) creditors required to endorse it. If not approved, the alternatives are voluntary administration; or liquidation (using the “simplified” process referred to above).

Okay, enough techy detail, how will this affect your regular fixed income investor?

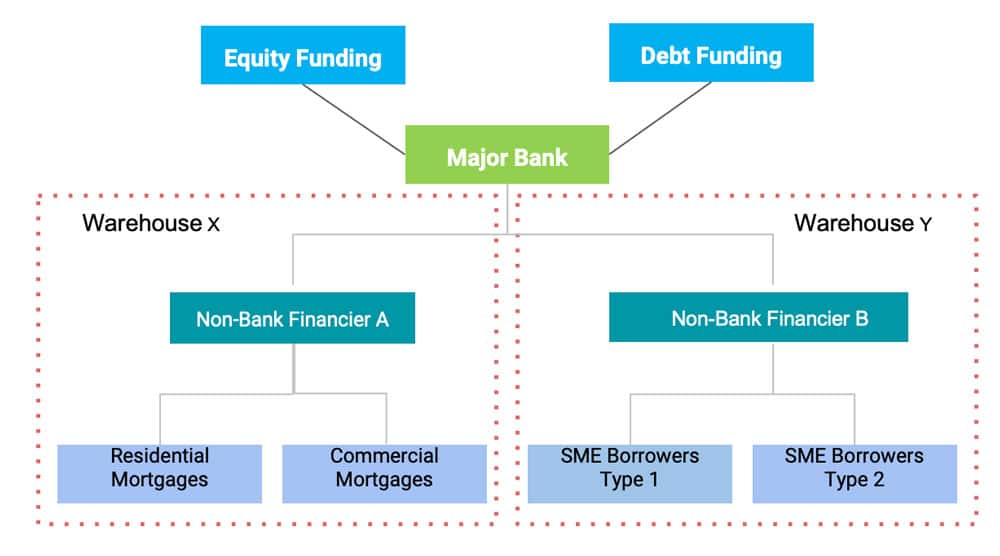

In essence, we must follow the chain of credit supply back up from the small business borrower, through the non-bank SME lender, up to the large scale warehouse providers. It is this supply chain which makes it very hard for governments to change one area of legislation, without it having knock-on effects elsewhere.

The SME borrower sources a small loan from a specialist financier such as On Deck, Moula, Credabl, or Octet. Those non-bank players typically seek a “warehouse” facility from a larger institution like a bank, to secure their own funding. In that warehouse, thousands of smaller loans are placed waiting for either refinance, or for a “term out” transaction whereby the bank creates a security with longer tenor, to sell into the bond market. Changes at the bottom of the chain ripple upwards. The diagram below helps to explain this process, with two different non-banks using warehouses from the same bank.

Source: Bishop & Fang

It appears from our conversations with industry practitioners that there was little to no government consultation prior to these changes, leaving scope for unintended consequences. The DIP approach for example echoes some of the mechanisms in the US market, representing a change to the philosophy of Australian insolvency law, which to date has been creditor-friendly. If creditors are indeed in a worse position, they will look to recoup that through higher lending rates. This in turn means funding will cost more for businesses. Lawyers, Hamilton Locke, among others, points out that this new approach may encourage “off balance sheet” funding, where risks are pushed away from SME’s towards other stakeholders. Again, these changes could come at the expense of higher lending rates.

If we follow the daisy chain up to the big banks, what costs will those banks seek to recoup from the non-bank financiers, in exchange for providing warehouse facilities?

What does this mean for the risk profile of the small business loan book – better or worse?

If the underlying pool of SME loans is now more risky, or the expected “loss given default” amount has increased, that should be reflected in a higher cost of funds. At the very least, while the banks and non-bank lenders wrap their heads around the changes, it will result in a longer and more uncertain underwriting process. More uncertainty is not what team Australia needs right now.