CPI inflation was just 0.2% in the September quarter, bringing the annual rate down to 2.8%. But don’t expect the RBA to celebrate inflation inside its target range with a big “mission accomplished” banner.

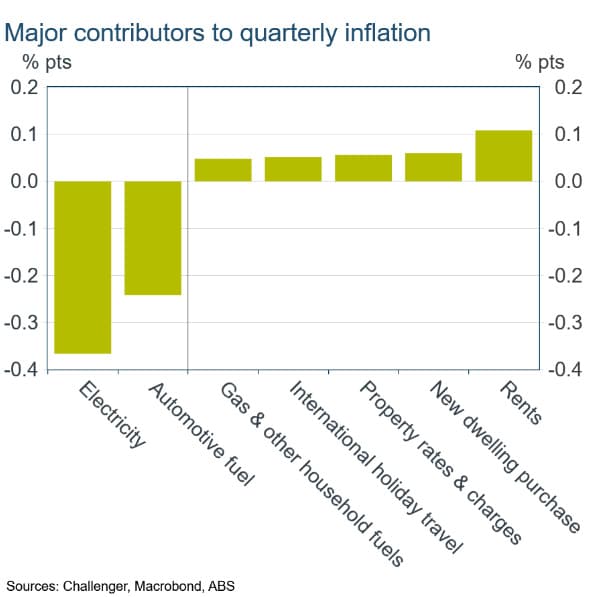

Electricity prices fell 17% in the September quarter but would have risen 0.7% without Federal and state government rebates. In other words, the electricity rebates subtracted about 0.4 percentage points from inflation in the quarter. Falls in petrol prices, following falls in global oil prices, also subtracted significantly from inflation. At the other end of the spectrum, the largest contributions to inflation came from housing components: rents, new dwellings and property rates. Inflation from rents and new dwellings is slowing but is likely to remain high given low additions to housing supply.

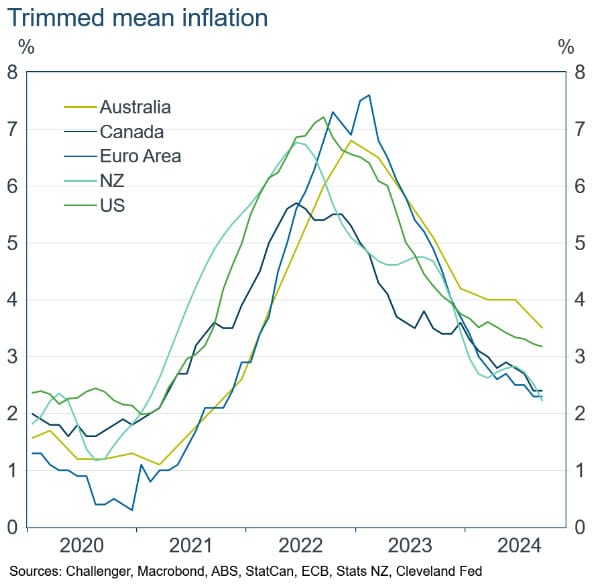

The RBA focuses on trimmed mean inflation which better reflects demand pressures and largely abstracts from policy changes and temporary shocks. Trimmed mean inflation slowed to 3.5% but it remains high compared to trimmed mean inflation in other countries.

Also read: Active Bond Managers On Track For Another Strong Year

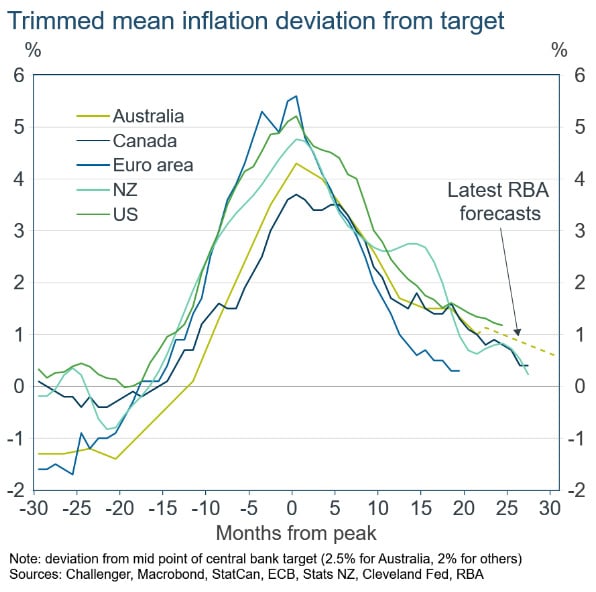

The higher trimmed mean inflation partly reflects that the peak in inflation in Australia was later than in other countries, and partly that Australia’s inflation target is higher than in other countries (2.5% vs 2%). Aligning inflation peaks and adjusting for the target makes Australia compare more favourably to other countries’ trimmed mean inflation.

This might raise hopes that the RBA can cut soon. Australian trimmed mean inflation peaked six months after Canada, and they first cut rates in June, and three months after the US peak, who first cut in September. Applying those lags would imply a December RBA cut. Inflation in Europe peaked after Australia, and they cut way back in June. Even New Zealand, where inflation peaked six months ahead of Australia, first cut in August suggesting an Australian cut in February.

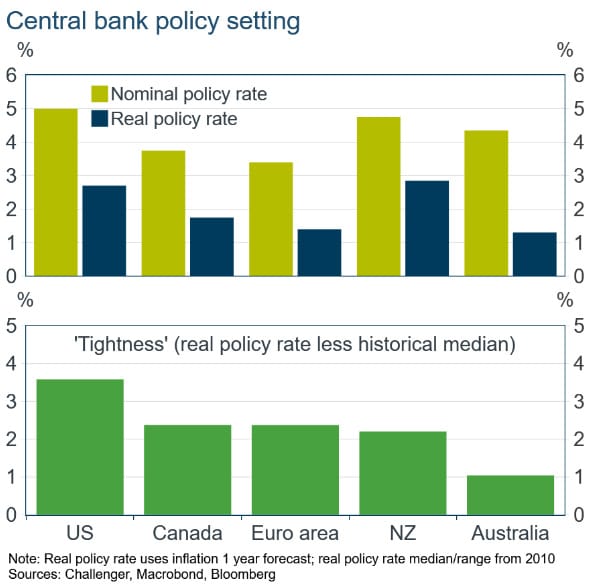

But don’t let a simple assumption that Australia is following the same path as other countries lull you in to expecting a Christmas or even Melbourne Cup rate cut. It’s important to note that other central banks tightened policy more than in Australia and so they have been earlier in removing their greater degree of restrictiveness. The Australian nominal cash rate is now above those in Canada and Europe. However, adjusting for forecast inflation, which is higher in Australia, the real policy rate in Australia is still much lower than in other countries. With a less restrictive policy setting, cuts in the cash rate will come later and slower, starting at best in the first quarter of next year.