As US direct lending continues to grow, the market is getting increased attention from actors across the financial system – not all of it favourable. Michael Smith Co-head US Private Debt, Muzinich & Co, explains why understanding the nuances is essential for investors considering an allocation to the asset class.

Key points:

The US direct lending market has expanded significantly, driven by institutional investors seeking higher returns and small businesses facing tighter bank lending standards.

- US direct lending has delivered annualized total returns of 9.5% since 2004, while defaults have remained relatively low compared to public markets, despite inflationary and interest rate pressures in recent years.

- Despite the strong performance, there are concerns about potential vulnerabilities in the market, including issues with creditor protections and loan valuations, particularly in the core and upper-middle market.

In the US direct lending market, where media coverage sometimes veers between hyperbole and hysteria, it pays to keep a level perspective.

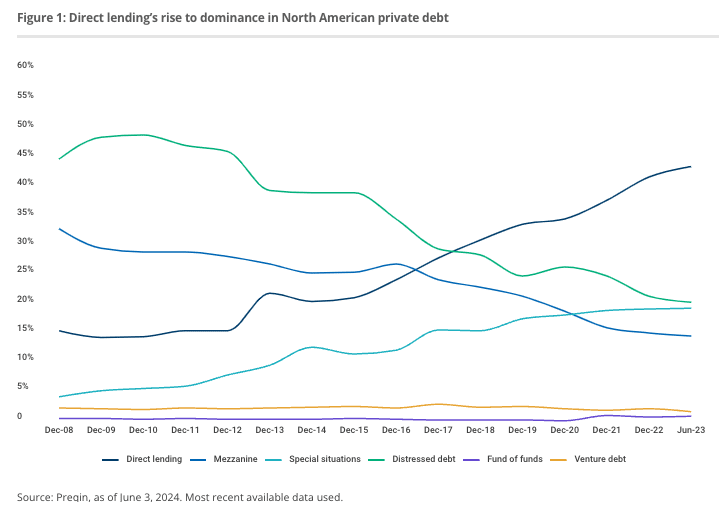

Let’s start with the facts: the US has been the driving force behind the growth of the direct lending market globally in recent years, with assets tripling from US$260.7 billion in 2018 to US$830.5 billion in September 2023.¹ The US accounts for 57% of the total, having expanded almost 250% over the same period (Figure 1).

The rise in direct lending is due to demand and supply factors. On one hand, institutional investors have been attracted to the market to capture a potential illiquidity premia over public markets and to diversify portfolios. On the other, small business owners have cited concerns over their access to capital,² as banks continue to tighten lending standards due to higher rates and stress in the commercial real estate sector.³

Growth in the asset class has been accompanied by strong long-term returns. Since its inception in 2004, the Cliffwater Direct Lending Index, which covers 15,600 US middle-market loans worth a combined US$337 billion, has seen annualised total returns of 9.5%.⁴

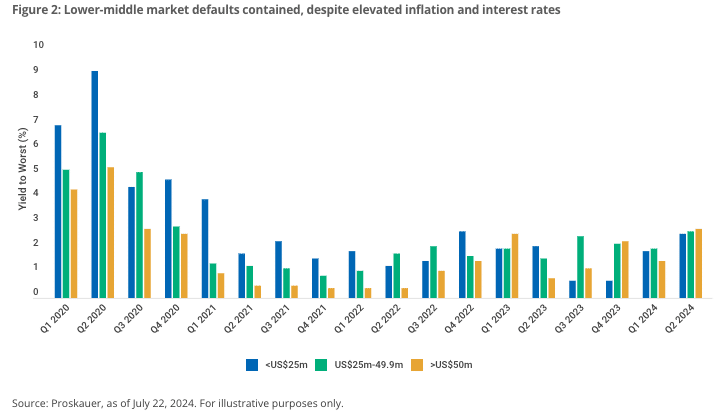

It is also true that defaults have been relatively contained since the onset of COVID-19 in 2020, particularly during a post-pandemic environment characterised by higher inflation and rising interest rates.

The Proskauer Private Credit Default Index, which launched in May 2020 and tracks almost 1,000 senior-secured and unitranche lower-middle market loans in the United States worth around US$150 billion, has seen defaults for all company size categories average less than 2% in the past 3 years (Figure 2). This compares favourably to the public market, where the trailing 12-month US speculative-grade corporate default rate was 4.8% at the end of March 2024.⁵

On the face of it, there seems little cause for concern. But this year, warnings about the broader private credit market have come from, among others, a prominent Wall Street CEO⁶ and the International Monetary Fund.⁷ And, in recent months, a possible debt restructuring of the private equity-owned tech education platform Pluralsight, after its sponsor reportedly marked down its equity value to zero and injected capital ahead of existing lenders collateralised by essential corporate assets, has raised concerns about the strength of creditor protections and loan valuations.⁸

So, where does the truth lie? Are the recent headlines a storm in a teacup or are vulnerabilities building beneath the surface? We put the key questions to Michael Smith, co-head of US private debt at Muzinich & Co.

Also read: Why Passive Flows and Inelastic Markets Don’t Mix

Where do you currently see opportunities?

Over the past decade, we have seen a tremendous amount of capital raised for private credit, particularly direct lending, due to investor demand and the prevailing shift among banks to move loans off their balance sheets. In the US, the direct lending market is largely driven by private equity sponsors, who tend to focus on the core and upper-middle market. This is despite the lower-middle market accounting for 50% of all sponsor- related transactions in the US in 2023.⁹ The non-sponsor component of the lower-middle market has received far less attention, and this is where we see significant opportunities. This is in part because traditional capital providers in this area – banks and small business investment companies – have steadily pulled back, and because many institutional investors have focused on larger transactions. So, you have traditional financing sources contracting combined with a need for capital – that push-pull dynamic makes it a compelling proposition, in my view. There is a potential opportunity to achieve a premium over the core and upper-middle market with typically less leverage than traditional direct lending deals.

Are there any noteworthy regional or sector nuances?

We see opportunities across the board. Year-to-date, our own deal origination is up around 18% (H1 2024 vs. H1 2023), which comes off the back of a very active 2023. We are continuing to see an increase in demand for capital. We focus on lending to individual companies with durable demand dynamics. Within that, we have seen attractive opportunities in healthcare services, IT and business services, and government contractors at the federal and state level. This allows us to construct a diversified portfolio we believe should be resilient even in difficult economic conditions.

As with any growing market, private credit is experiencing attention from regulators and multilateral agencies, including the IMF, which says the market “warrants closer oversight.” What are your thoughts?

To answer that, it is important to understand the historical context as to why banks are subject to tighter regulatory scrutiny. You can go back to what happened during the Great Depression, the Savings and Loan Crisis and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. The purpose of bank regulation is to protect depositors wanting a safe place to put their money. Layer in the fact that banks are highly leveraged organisations that have occasionally taken excessive risk, and it becomes understandable why you need guardrails. In the case of private credit, asset managers play a vital role in providing flexible financing to private companies, many of which do not enjoy the same access to bank capital as they did in the past. And while there is leverage in the market, you are not drawing on the capital of unsuspecting depositors. That is the fundamental difference between private credit and banks. The capital largely comes from sophisticated institutional investors making conscious decisions to invest in private debt strategies. There is an alignment of interest between all parties – borrowers need to meet their obligations to lenders if they want to maintain access to funding, and lenders need to have underwriting discipline and deliver the expected outcomes to build lasting relationships with their clients. Failing to deliver will have consequences for those managers.

We are still waiting for the Fed to cut rates, but even when it does, the expectation is that they will remain higher for longer. What are the implications for US private credit?

There are a few ways to look this. For direct lending strategies, higher-for-longer potentially means higher potential returns for investors. The flip side is that borrowers who were already highly levered when base rates were lower will continue to face pressure given the floating-rate nature of the loans. We have seen evidence of this, particularly in the core and upper-middle market, as interest rates have risen in the past couple of years and some borrowers face liquidity challenges. However, many of these companies are essentially good businesses who are stressed rather than distressed – there is a big distinction between the two. They will need to work with lenders to get their balance sheets into a healthier state, which could present opportunities for capital solution-type strategies. Higher-for-longer will also impact M&A, which means capital deployment for purely sponsor-focused strategies will likely remain muted. Additionally, it could precipitate further stress among smaller banks, which we believe will create potential opportunities in the non-sponsor part of the lower-middle market.

Recently, we’ve seen a situation that has put a lot of scrutiny on covenants and creditor protections. What’s your take and how prevalent is this issue in the market more broadly?

My first observation is that there can be significant overlap in the portfolios of larger core and upper- middle market direct lending strategies. If you take the Pluralsight example, its first-lien unitranche loan is common to seven business development companies (BDCs) managed by some of the largest players in the market.¹⁰ Both of those loans feature in five BDCs managed by a single lender.¹¹ While the exposures are relatively small given the size of the portfolios, if we started to see more of these situations emerge and similar overlap in terms of exposures among managers, it could have a real negative impact on the returns of some of those strategies. With the lower-middle market, you tend to find loans that are less common to a specific portfolio so there is generally less correlation between portfolios from a single borrower perspective. One other relevant point on Pluralsight is that the sponsor was able to encumber assets lenders thought were part of their collateral package. In my view, a reduction of structural protections in loan documentation is an issue in upper-middle market private credit, where increased competition among lenders for the same assets has allowed these terms to creep in. In the lower-middle market, there is less competition and thus more power to negotiate tighter credit protections.

References

1. Preqin, ‘Strategy in focus: Direct lending’, as of June 3, 2024. Most recent data available used.

2. Goldman Sachs, ‘Glass Half Full’, January 31, 2024

3. Federal Reserve, ‘Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey, April 30, 2024

4. Cliffwater, as of March 31, 2024

5. S&P Global, as of May 16, 2024

6. Yahoo Finance, ‘Wall Street is divided over the rise of private credit’, as of June 16, 2024

7. International Monetary Fund, ‘Fast-Growing US$2 Trillion Private Credit Market Warrants Closer Watch’, as of April 8,2024

8. KBRA, as of June 5, 2024

9. Pitchbook, US PE Middle Market Report 2023, as of March 14, 2024

10. References to specific companies is for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect the holdings of any specific pastor current portfolio or account.

11. KBRA, as of June 5, 2024