Paul O’Connor, Head of Multi-Asset, Janus Henderson Investors, considers the prospects for growth and interest rates as we move into the final few months of a seismic year for global financial markets.

Although we are still only three-quarters of the way through 2022, it is already clear that this will be a memorable year in global financial markets. Many investors are experiencing economic and market phenomena this year that they have never encountered before in their careers, such as double-digit inflation, aggressive interest rate hikes in major economies and simultaneous bear markets in equities and fixed income. While markets are often regarded as being prone to over-reaction, this claim seems less valid this year, with market turbulence reflecting investors’ struggles to price in the impact of exceptional developments in the real world, such as the war in Ukraine, the lingering effects of the pandemic and dramatic shifts in global monetary and fiscal policy.

Nowhere to hide

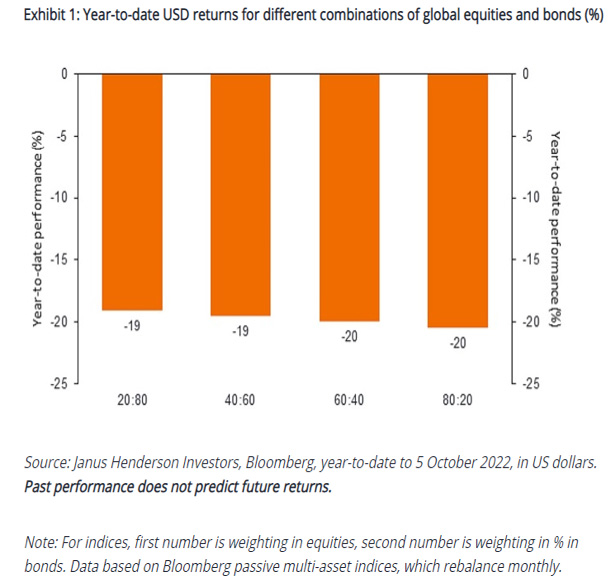

Investors have had nowhere to hide among mainstream financial assets this year. At the end of Q3, the majority of the world’s major indices were registering double-digit losses in most categories of equities, corporate debt, and government bonds. While some commodity markets are still showing positive returns for the year, most of these peaked in Q2 and have seen double-digit drawdowns since then. The performance of passive multi-asset indices highlights the unusual nature of the challenge facing investors in 2022 (Exhibit 1). What is most striking here is that the broad range of different benchmarks have delivered such similar returns, in US dollar terms this year. At the end of Q3, a US investor with 80% invested in passive bonds and just 20% in equities would have been experiencing similar portfolio losses for the year as an investor with the opposite portfolio structure.

From a financial markets perspective, the ultimate impact of this year’s marked economic and political developments largely boils down to how they have influenced interest rate and growth expectations. Markets have struggled as the outlook on both fronts has deteriorated this year. Although significant progress has been made on recalibrating expectations in recent months, we do not yet see compelling evidence that the market adjustment to a regime of higher rates and weaker growth is yet complete to make us confident that the bear market in stocks has run its course.

Also read: Australian Economic View – October 2022: Janus Henderson

Downgrades loom

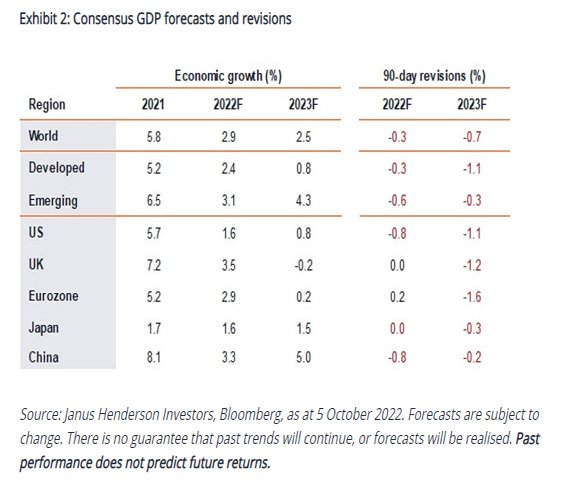

Where the growth story is concerned, consensus economic forecasts show that the developed economies are now rapidly losing momentum, with the outlook for next year looking fairly grim. Projections of real GDP growth for 2023 are now at 0.8% for the US, 0.2% for the eurozone and -0.2% for the UK. These projections are far from stable and have been persistently downgraded this year as economists get to grips with the adverse impact of the cost-of-living squeeze on consumer spending. With commodity prices generally falling in recent months, and governments introducing various fiscal initiatives to cushion consumers from surging fuel bills, this theme is probably now well factored into consensus estimates.

However, it seems unlikely that the impact of rising interest rates is yet in the numbers. Monetary policy famously affects the economy with “long and variable lags” and the interest rate shock in the major economies is far from over. Whereas policy rates in the eurozone, the US and the UK were not far above 0% for most of 2020 and 2021, they are now expected to peak at around 2.75%, 4.5% and 5.5% respectively in 2023, as sizeable rate hikes are pushed through in the next few months. Economists might well have factored in the first-round impact of the commodity squeeze on economic growth but may probably spend the next few months downgrading projections further as momentum falters in housing and other interest rate sensitive areas.

While economists have been cutting growth estimates all year long, equity analysts have a lot more work to do. Consensus forecasts for global earnings growth remains fairly upbeat at 11% for this year and 6% for next. Rising commodity prices and inflation may have underpinned earnings momentum in some sectors until now, but cost-driven margin pressures and cooling demand are likely to weigh more heavily in the months ahead. In a typical recession, analysts generally downgrade earnings growth by more than 20% from the peak. So far, in this cycle, analysts have downgraded earnings from peak estimates by only 6%. While reasonable arguments can be made to suggest that the global economy is not about to slump into a typical recession, many reliable models suggest that at least a shallow recession should be the central scenario from here. Even on this outlook, analysts’ earnings estimates look too high and big earnings downgrades seem imminent, as the economy loses momentum in Q4 and early next year.

Interest rate expectations are close to a peak

More progress has been made on adjusting interest rate expectations this year than on the growth side. Indeed, after this year’s aggressive repricing, we feel that the upside to interest rate expectations is now more limited, with market estimates of peak rates now at levels that economies seem unlikely to be able to withstand for very long. Central banks will probably remain reluctant to signal that the interest rate cycle has peaked while core inflation is still trending higher, but markets are likely to pre-empt a policy shift if growth loses momentum in the months ahead, as we expect. While central banks in the eurozone, UK and US look set to push through some sizeable interest rate hikes before the year end, our central case for these economies is that the peak in policy rates will be reached in the early months of 2023, not much higher than where rates reach by the end of this year.

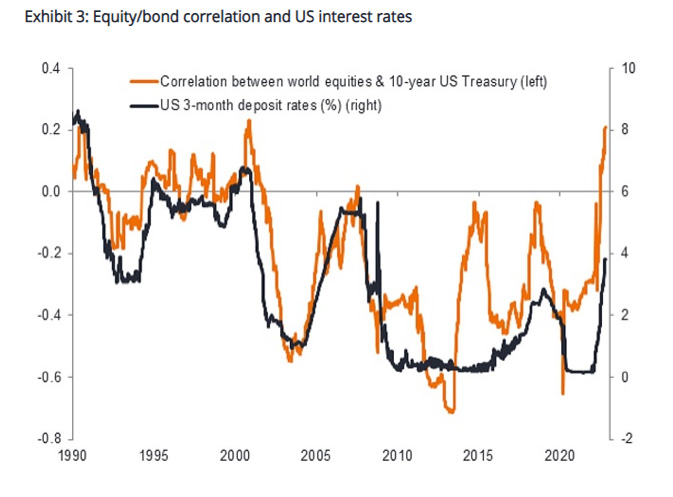

In recent months we have faded out our long-held negative view on bond duration on the multi-asset team and now believe that a more neutral stance is appropriate. Although government bonds have sold off hard this year, alongside risk assets, this is a typical phenomenon when the interest rate cycle is in an upswing. As we approach the peak in rates, we expect that the correlation between government bonds and risk assets to weaken, allowing the former to regain their diversifying characteristics in multi-asset portfolios.

Patiently underweight risk assets

Where risk assets are concerned, the outlook for Q4 remains somewhat murky. While the prospect of an imminent peak in interest rate expectations, against a backdrop of rapidly slowing growth, is a constructive one for government bonds, it is a good-news/bad-news mix for equities and corporate debt. Valuations are attractive in these asset classes after this year’s de-rating, but they do not, in our view, yet look sufficiently cheap to provide a strong case for rebuilding exposures. With growth downgrades likely to provide persistent headwinds for risk assets in the months ahead, we retain a cautious view of risk assets, although we find more reasonable value across higher-quality credit markets now. In broad terms, we would highlight two conditions that probably need to be met before we can get more strategically constructive on risk assets. One is that we get more confident that markets have priced in the peak in the interest rate cycle. The other is that we get more confident that markets have factored in more realistic growth expectations. Capital preservation should remain a key focus until at least one of these conditions has been met.

So, we enter Q4 regarding this year’s two big themes – the repricing of growth and interest rate expectations – as unfinished business for financial markets. However, we see progress on the latter as now being fairly well advanced. From here, we are less concerned about interest rate risk than we have been for most of the year, but we do remain wary of risks associated with slowing growth. Headline inflation has probably already peaked in the major economies but progress on core inflation, service sector inflation and wage growth could likely be the most important drivers of broad risk appetite in the months ahead. An easing of inflation on these measures should take the pressure off central banks, interest rates and financial markets. Alternatively, if underlying inflation remains stronger for longer than we expect, then the bear markets in equities and bonds will probably have further to run.

China is the wildcard

Beyond these cyclical dynamics in the major economies, we still see China as a potential wildcard for the world economic outlook from here. Developments in China have not had a notable impact on global market sentiment this year, with so many other key dynamics at play. However, they still retain the scope to play a more emphatic role in the final months of 2022 or next year. While consensus forecasts show a significant rebound in Chinese growth in 2023, as some of this year’s drags recede, these projections seem less reliable than ever, given the uncertainty surrounding the unfolding property correction and its potential economic and financial spillovers. Decisive policy intervention will almost certainly be required to diffuse this difficult situation. The next steps for the Chinese government on this front and on their zero-COVID policies have scope to meaningfully change the outlook for Chinese growth, to the extent that China becomes, once again, a key driver of sentiment in global financial markets.