By Robert Almeida, Portfolio Manager and Global Investment Strategist at investment giant MFS Investment Management. . Established in 1924, MFS manages US$601.3 billion in assets on behalf of individual and institutional investors worldwide (as at January 31, 2020).

- Negative real yields have unmoored asset prices from fundamentals.

- Mounting, though transitory, inflation pressures are likely to start pushing real yields higher.

- Higher real yields should feed into lower risk asset valuations.

In the United States, the economy has recouped nearly all the ground lost during the pandemic, and corporate earnings aren’t far behind. As I wrote in March’s “A Year Like Few Others”, risk assets have discounted this V-shape recovery, but as economic and earnings data evolves from forecast into fact, markets are looking ahead to see what’s next.

And I believe what’s next will be a day of reckoning as investors grapple with higher yields. Here’s why.

Every investment opportunity is ultimately weighed against competing possibilities for use of funds. The decision to allocate capital happens only if the investment will clear its hurdle rate. While the height of every investment hurdle is determined by its idiosyncratic risk, real, inflation-adjusted interest rates are the first input into that calculus.

Anchors aweigh

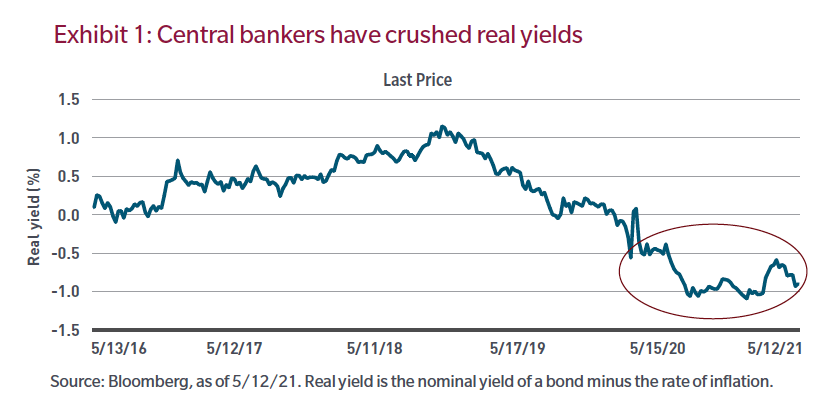

During the 2020 recession, central bankers were determined not to allow lockdowns to morph into a credit crisis. In order to buoy animal spirits, policymakers removed the first rung in the ladder of every hurdle equation by driving real US Treasury yields deeply into negative territory, as illustrated in Exhibit 1 below.

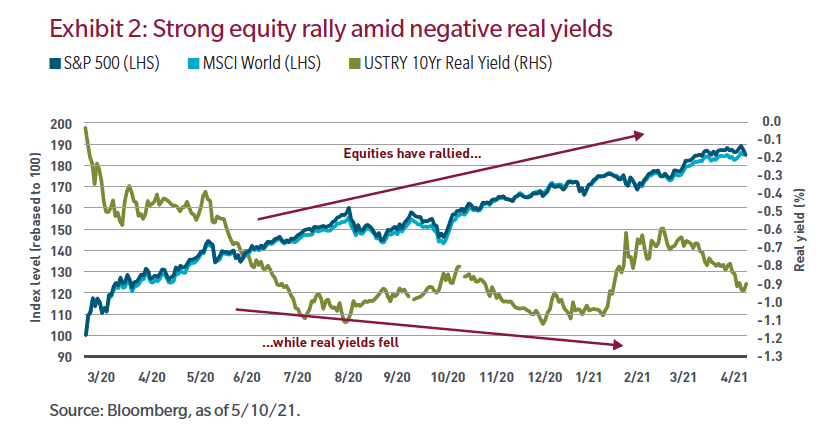

However, financial theory holds that asset prices are lognormal, meaning they can’t go negative. Since capitalism requires a hurdle rate, business schools or CFA prep courses don’t teach students how to value a company or a project with negative nominal or real interest rates. Without an anchor, it’s apparent why risk assets have risen as they have. Exhibit 2 overlays the advances made by the S&P 500 and MSCI World indices from their pandemic lows against the path of U.S. 10-year Treasury real yields into negative territory.

While there’s much sell-side research contending that risk assets can absorb inflation and higher rates, there’s an observable inverse correlation in the chart above that I think is causal and not coincidental. Since rates are the first hurdle in the valuation of any asset, higher rates, whether real or nominal, lower the value of that asset.

What’s next?

As economies continue to reopen and excess savings are spent, inflationary pressures will continue to mount. We’re seeing it in goods such as lumber, semiconductors and automobiles; in services such as airfares, rental cars and vacation rentals; and in hard assets such as commodities and real estate.

Ultimately, we believe these pressures will prove transitory as the secular disinflationary forces of the past decade-plus — elevated debt levels, aging demographics and continued digitalization, to name three — reassert themselves. However, we’re confident that negative real rates are unsustainable and will eventually normalize. What we’re less confident about is the timing or the rate at which real yields will rise.

Regime shifts are always clear in hindsight but rarely at the point of inflection, yet markets have a way of sniffing them out. And when they do, we suspect that the relationship displayed in Exhibit 2 will reverse as rising real yields undermine equity valuations. As we go from forecast to fact, we believe market performance and leadership will look materially different than they have in the past several quarters.