From Amundi Asset Management

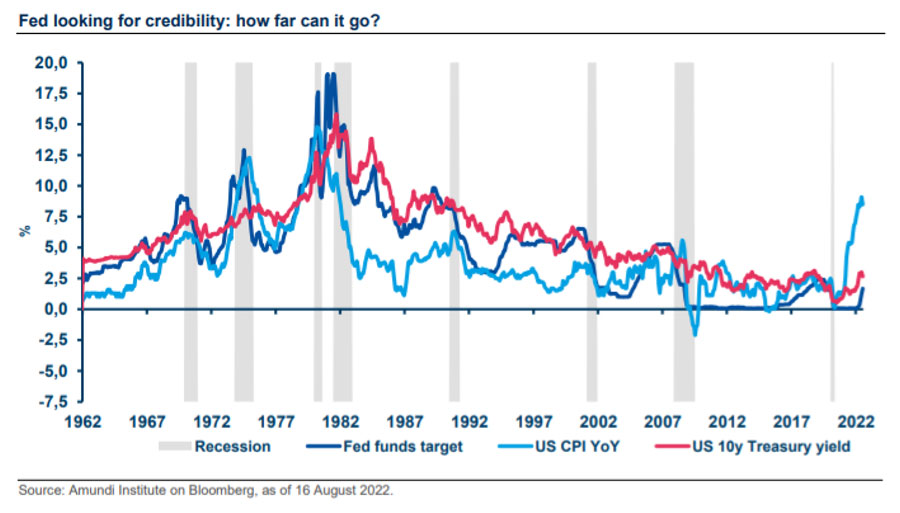

Investors expect central banks will tame inflation whatever the cost, even triggering recession if necessary. This may indeed be policymakers’ approach in the short term as they seek to re-establish their credibility. The European Central Bank’s decision to raise rates by 50 bps is a case in point. While that could cement investors’ views of how rate-setters will act in the longer term, they risk overestimating central bankers’ ultimate willingness to hurt growth. What’s more, financial markets are misjudging how long it will take economies and consumer prices to respond to increases in interest rates.

Inflation shows few signs of subsiding, and while activity may be slowing economies continue to grow. That’s understandable given monetary policy is still relatively accommodative, despite recent rate rises, and financial conditions remain easy. Yet markets are focused on the risk of an imminent collapse in growth; this may be a case of getting ahead of ourselves.

Even assuming central banks hike rates rapidly to a more neutral level, it takes time for the effects of such tightening to filter through to the economy. We may have to wait anywhere between a year to 18 months for rate rises to really rein in demand. There will then be another lag before consumer prices respond to this slowdown. As a result, inflation may exceed policymakers’ targets for another 10 to 15 months even after growth hits the skids.

All this presumes rate-setters are willing to induce a recession to meet their mandates. But in my view, they will balk at inflicting too much pain on the economy. Inflation will therefore be higher than many expect over the next couple of years, with important implications for asset prices.

Also read: Investors Focusing On Defensive Positions & Inflation-Resilient Assets

In fixed-income markets, this will mean even higher yields. While recession worries have flared recently, the outlook for growth can only be the dominant driver for bonds if inflation is quiescent. Given that won’t be the case, yields will rise. Take, for example, the benchmark 10-year U.S. government bond. Assume its yield can be decomposed into two basic components: the 10-year average of nominal U.S. growth, and a risk premium. That long-term nominal growth rate may previously have been around 4% – the sum of 2% real growth and inflation of roughly 2%. We therefore wouldn’t be surprised to see the 10-year Treasury yield rise to 4% or above. While this adjustment process happens, being flexible in duration management will be the name of the game.

Higher average inflation rates could also weigh on stock markets. The price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P 500 may drop another point or two, which implies another 10% to 15% decline in the index itself. Rising borrowing costs and falling equity values pose risks to companies that have taken on huge amounts of debt in recent years. However, high-quality credit has adjusted more quickly than equities to the shifting outlook, and may be less vulnerable.

Emerging markets present a slightly different picture. Central banks in many of these countries responded more swiftly to accelerating inflation than their developed-market peers. Their monetary policy tightening may be nearly at an end, and some of them offer attractive inflation-adjusted interest rates.