Credit ratings are important indicators of risk and return in fixed income markets.

They give investors an indication of the perceived future risk they are taking and measure the perceived risk of future failure to pay promised income or capital at maturity.

A high credit rating, in the AAA, AA or A range means a low-risk investment with a corresponding low-interest rate, while a low sub-investment grade rating such as CCC, CC or C is deemed very high risk and thus pays a high-interest rate.

There are three main international credit rating agencies – S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s and FitchRatings.

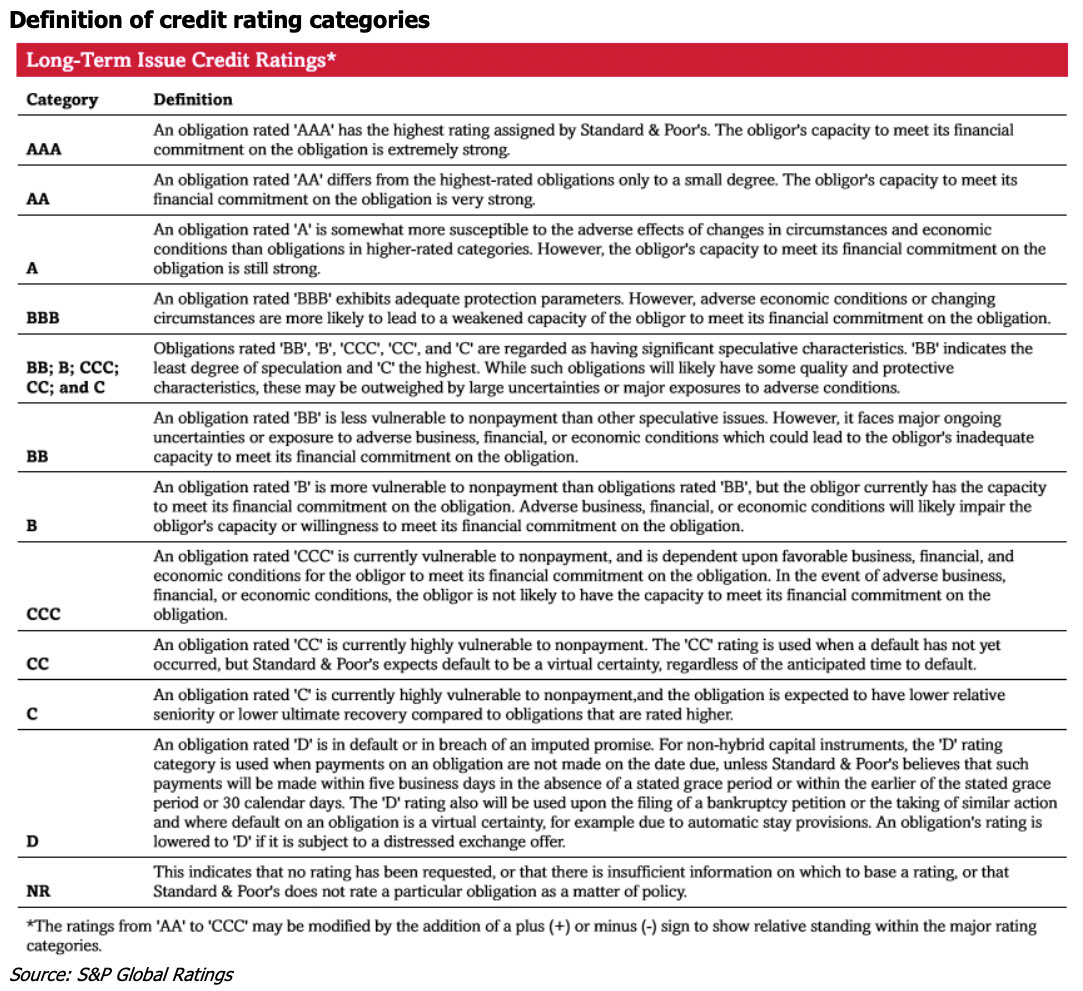

In Australia, Standard and Poor’s Global (S&P) is the prevalent credit rating agency. Its credit rating scale differs from the other main agencies. See the S&P Global credit rating definitions below.

It is important to note the AA measure down to the CCC measure above, can be further defined using (+) and (-) at each level.

While useful in your assessment of various bond issues, credit ratings should not be the only way you assess risk. During the GFC, some ‘AAA’ rated securities defaulted.

The credit rating at first issue, is one of the key factors that will help determine the interest rate payable on the bond. Others include the term to maturity, the issuer and where the issuer is domiciled.

After bonds have been issued and are trading in the secondary market you can sometimes see yields and credit ratings out in sync. Bonds that show much lower or higher yields than what is typical for the credit rating band, are often expected to be re-rated. Sometimes the market has the bond assessment wrong. In any case, it is worth doing your research to make your own assessment.

It is important to remember, companies pay to have bonds and other debt securities rated. Smaller companies or those with sub investment grade characteristics may chose not to pay for a credit rating. Size, geographic and product diversity matter in calculating a credit rating, so small, concentrated companies would expect sub investment grade credit ratings in any case.

Credit ratings and the capital structure

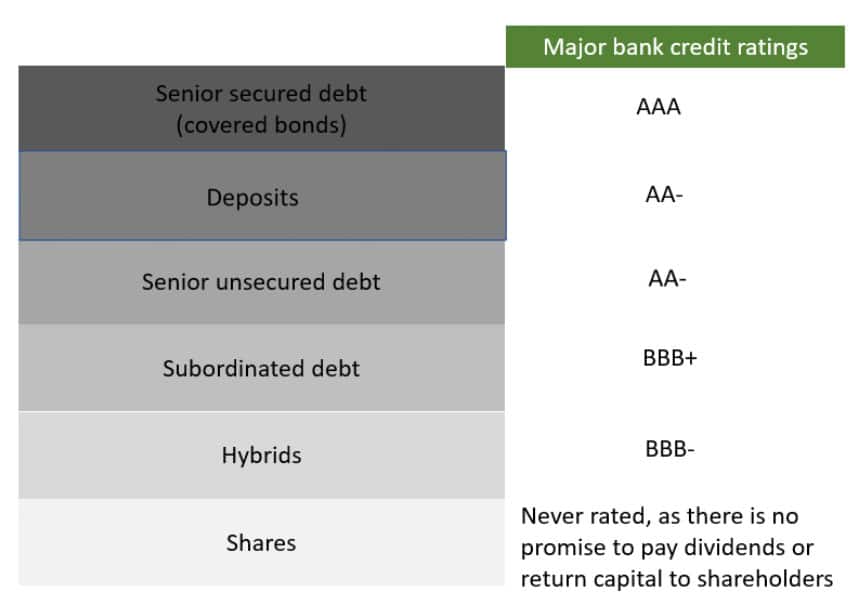

When you read a company credit rating, it refers to the senior unsecured level in the capital structure.

But bonds can sit higher and lower in the capital structure. Thus, it is reasonable that the three levels of bonds and lower-ranked hybrids in the capital structure within the same company all have different credit ratings.

Some investors take the credit rating and apply it to their shareholdings. But shares do not promise to pay an income, although there is often an expectation, and shares do not have a maturity date. So, credit ratings can never apply to shares that do not promise anything!

A company might have hundreds of bonds that could be issued at a higher or lower level in the capital structure than the senior unsecured level. So, understanding where bonds sit in the capital structure with the credit rating should help your understanding of the risk of an individual bond or debt security. Risk increases moving down the capital structure. See a sample of major Australian bank credit rating levels in the capital structure below.

Source: FINA, Bloomberg

Credit ratings and the probability of default

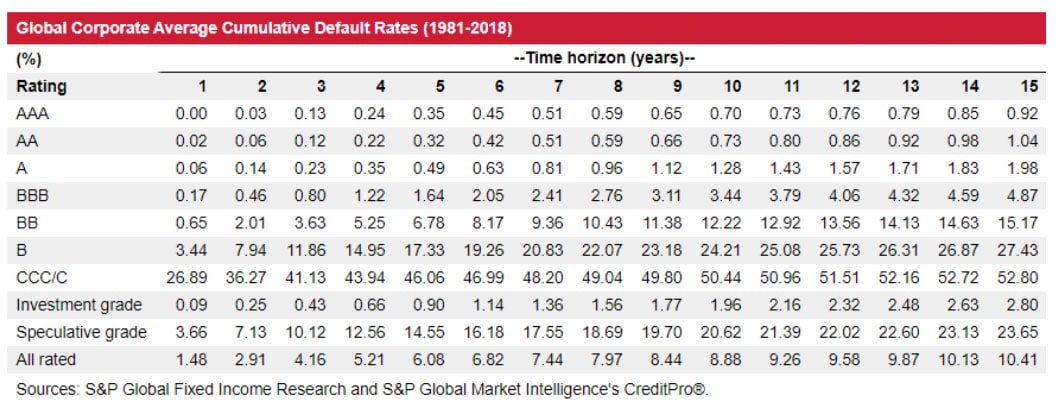

Over many years, S&P has tracked the default rates by credit rating, so that investors can understand the probability of default.

Below is the Global Corporate Average Cumulative Default Rates from 1981 to 2018. That means percentages at year five are across the full five-year timespan and at year 10, across all ten years.

Many bonds are issued over 5-year timespans, so let’s look at that column in detail.

Starting at the AAA credit rating over five years, run your eye down the column. You can see, with the exception of the AA credit rating band, that the probability of default rises as credit ratings decline.

There is quite a big jump from single ‘A’ to ‘BBB, going from 0.49% to 1.64%, but then an exponential jump as we head into sub-investment grade or high yield ratings at BB which is 6.78%.

Keep going down the list and a single ‘B’ credit has a 17.33% probability of default over five years, CCC through to single C, 46.06%.

You begin to appreciate the differences between investment-grade credit ratings and sub-investment grade.

Across all investment-grade credit ratings, the probability of default over five years is less than 1% at 0.90%. For sub-investment grade/ high yield this jumps to 14.55%.

These differences warrant higher returns and as investors, we need to determine if the extra risk we take by moving down the credit rating scale is properly compensated for by the return.

What constitutes a default?

For the purpose of the S&P study, a default is recorded the first time a payment default on any financial obligation whether it is rated or unrated – other than when it is due to a bona fide commercial dispute.

There is an exception when the interest payment is missed on the due date, but is made within the contracted grace period.

Preferred stock is not considered a financial obligation, so a missed preferred stock dividend is not normally equated with default.

Distressed exchanges are considered a default; that is when bond holders are coerced into accepting substitute instruments with lower coupons, longer maturities, or any other diminished financial terms.

S&P deems ‘D’ (default); ‘SD’ (selective default); and ‘R’ (under regulatory supervision) as defaults for the purpose of the study.

For more information see the excellent explanations and videos at https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/about/understanding-credit-ratings