The US high-yield credit market has been a reliable asset class for investors growth fixed income allocations over the past decade. Grant Webster, Co-Head of Emerging Market & Sovereign FX, Ninety One, warns of potential disappointment ahead and outlines why an allocation to emerging market debt looks like an attractive alternative.

Following an exceptionally strong 10-year run in the US high-yield credit market, there’s a significant chance the asset class will fail to meet lofty expectations over the coming period. In contrast, emerging market hard currency debt could give investors what they need and prove to be a more reliable allocation. Considerations that point to a more favourable outlook for EM debt than for US high yield fall into three broad categories: valuations, fundamentals, and market technicals.

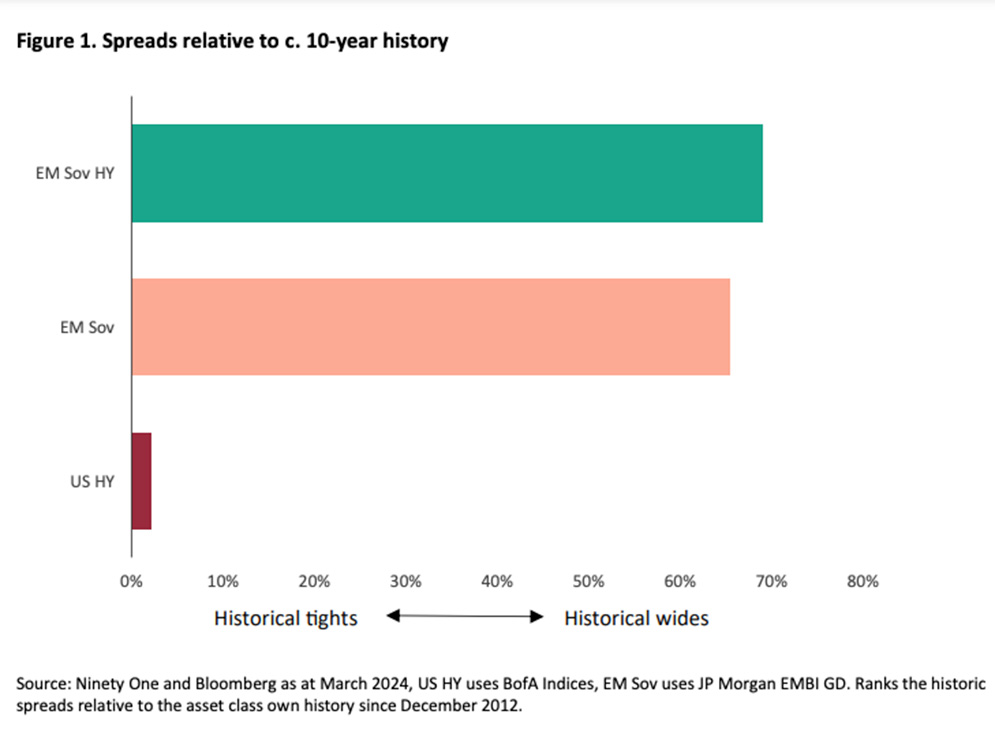

When comparing valuations, it is useful to look at spreads relative to an asset class’s 10-year history. As the chart illustrates, following a stellar decade, spreads in the US high-yield market are almost the tightest they have been in that time frame. By contrast, EM sovereign debt valuations appear significantly more compelling, with spreads close to the widest they have been in the past decade.

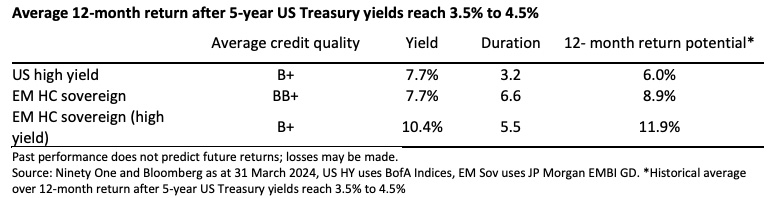

Historical analysis of yields can also provide useful insights. Grant Webster, Co-Head of Emerging Market & Sovereign FX, Ninety One: “History shows that yields tend to be a useful indicator of forward-looking returns in fixed income, as we noted here. Today, the high-yield EM hard currency sovereign debt market offers a yield c.2.7% higher than the US high-yield market, suggesting a more favourable risk-adjusted return outlook for an EM debt allocation. From a more cyclical perspective, history has also shown that following regimes when US Treasury yields have peaked, the 12-month forward return was historically higher in EM, with the asset class’s longer duration particularly supportive. This points to a more favourable period ahead for EM debt than for US high-yield debt.”

Also read: The Year of the Bond Is Hard Going But Coupon Income Could Save The Day

Looking at fundamentals and default rates, EM sovereign defaults have stabilised following the significantly above-trend default rates seen across more vulnerable markets between 2018-2022. This is reflected in improved asset-class performance in 2023 and this year to date. The cohort of surviving EM economies are robust, benefiting from prudent monetary policy and manageable debt maturity walls. Yet current valuations suggest that the market is already pricing in ample compensation. In contrast, although US high-yield market default rates are benign, there a signals that challenges could be on the horizon.

Here are the key considerations when weighing asset class resilience for the next chapter:

• Emerging markets: Across EM economies, fiscal strength is seeing the biggest improvement, with increasingly healthy primary fiscal balances. Funding strength is better than in the pre-2012 period, thanks to growth in local funding markets, and external resilience is improving post-COVID on stronger basic balances (current account + FDI). The economic growth premium of EM relative to DM remains intact and above its long-term average. EM economies are in a good position structurally.

• US high-yield market: Trends in bank-lending standards have historically proven dependable bellwethers; a tightening in bank lending standards has historically been strongly correlated with defaults over the subsequent few quarters. With tight conditions persisting, the prospect of rising defaults among US high-yield issuers is a key risk factor for asset allocators to consider. Related to that, an important development over recent years has been a relaxation of covenants in the US highyield market; the result is that the recoveries on defaults in the US high-yield market are now much worse than the historical average.

Last but not least, the ‘technical’ tide appears to be shifting in favour on EM debt. In 2023, net flows into the EM hard currency sovereign debt market were deeply negative, compared with broadly flat net flows into the US high-yield market. Webster concludes: “As capital flows back into EM this should be supportive for the asset class. In contrast, the tide that has lifted the US high-yield market is on the wane. Over recent years, there has been a massive reduction in US high-yield issuance, while demand has been strong – with investors flocking to the asset class to chase returns. This has been compounded by the ‘rising star effect’ as the supportive environment for asset class resulted in a big portion of the index being upgraded to investment grade, reducing the size of the high-yield market and meaning more money is chasing fewer assets. The combined effect of a fading of the significant headwinds facing EM debt and tailwinds supporting US high-yield debt could lead to a big shake up in markets.”

The opportunity set in EM extends well beyond that of sovereign issuers, with corporates and quasi-sovereigns offering investors access to the compelling issuers with robust fundamentals and attractive valuations. The inclusion of a wider opportunity improves diversification and bottom-up selection opportunities.