Whether there’s a soft landing, hard landing, or no landing at all, it’s been a big question for financial markets.

What is a soft landing?

A soft landing is a slowdown in the economy, without a recession. This is opposed to a hard landing in which a recession results in the economy. Central banks wanting to bring down inflation, have lifted interest rates significantly, which have the impact of putting the brakes on the economy.

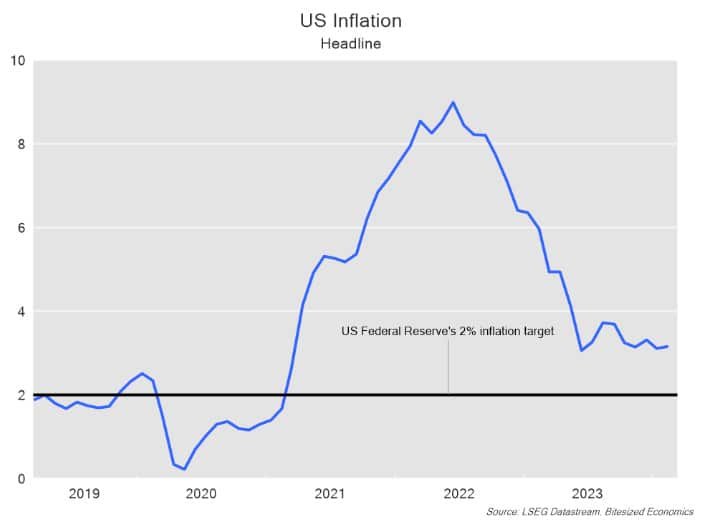

In the US, inflation has fallen significantly from a peak of 9% in June 2022, but it has been stuck just above 3% for the last nine months. Data this week showed inflation at 3.2% in February.

Has progress on bringing inflation down to the US Fed’s 2% target stalled?

It increasingly appears that way. If so, the Fed’s elusive soft-landing scenario comes into question.

Could the Fed still achieve a soft landing and avoid a recession? The jury is still out, but the odds of a soft landing are still higher than a year ago.

LISTEN: PODCAST: Is 2024 the year of the bond? with Janu Chan from Bite-Sized Economics

In this article, I look at the times in which the Fed did achieve a soft landing and draw some lessons for today for investors.

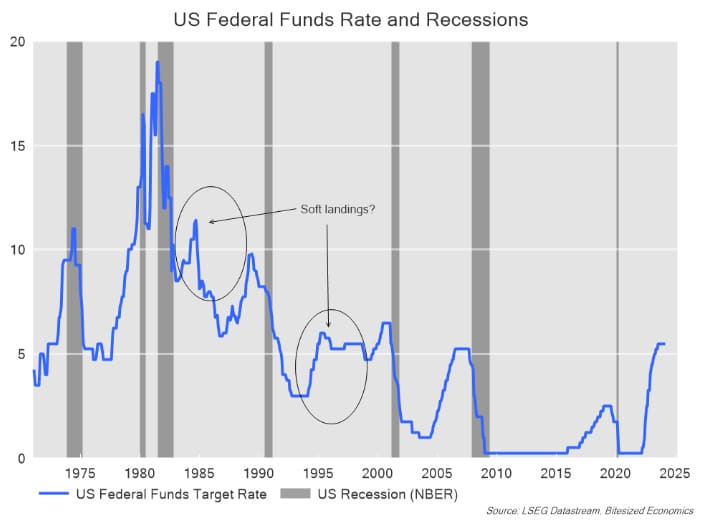

Note that soft landings have been rare. Over the past 40 years, there have been two instances when the US Federal Reserve has embarked on a tightening cycle and a recession has not followed – once in 1984 and once again in 1995. That equates to two out of nine rate-cutting cycles over that period.

So, while the Fed hasn’t had a great track record of achieving the soft landing scenario, they aren’t unprecedented.

Here are five takeaways from the ’84 and ’95 soft landings:

1) The fed funds rate didn’t stay at its peak for very long: In 1984, the fed funds rate touched a cyclical high at 11.4% in August before declining immediately after. In 1995, the fed funds rate topped out at 6% in March 1995, and rates were reduced just four months later in July.

2) Equity markets and bond markets performed well: Naturally, the prospect of falling interest rates supported equity markets and bond markets. The year 1984 wasn’t a particularly great year for equities, but the S&P500 saw a 26% increase the year after. The US S&P500 gained over 30% in 1995, the year when the fed funds rate peaked and began to decline. As expected, bond yields peaked soon before the Fed began cutting rates on both occasions.

3) When rate cuts eventuated in the 1984 and 1995 monetary cycles, the US economy had already shown substantial signs of slowing: The US economy had slowed from above 8% annualized growth over much of 1983 and the first quarter of 1984 to an annualized 3.9% pace in the third quarter of 1984. Similarly, US economic growth slowed from an annualized pace of 4.7% in the fourth quarter 1994 to 1.4% in the first quarter 1995 and 1.2% in the second quarter.

4) Inflation was still relatively elevated: While economic growth had indeed weakened by the time the Fed had pulled the trigger on rate cuts, the same can’t be said about inflation. Inflation had edged down from a peak of 4.9% in March 1984, but remained above 4% by August, when the Fed began cutting interest rates. In 1995, inflation was around 3% in June after peaking at 3.1% in April.

5) Rate cuts did not necessarily occur in quick succession and could reverse: This scenario is more a reflection of the 1995 rate-cutting cycle – the Fed took its time lowering interest rates. After the peak in the Fed funds rate of 6%, the Fed lowered rates a total of 75 basis points from July 1995 to 5.25% in January 1996. The Fed then left rates on hold for over a year until March 1997, until they lifted rates 25 basis points to 5.5%, and didn’t resume lowering rates until the second half of 1998 to a cyclical low of 4.75%.

Also read: How Bonds Are Faring In The New Inflationary Environment

Lessons for today

We can understand why some economists may want to see rate cuts sooner rather than later, which would prevent a more severe slowdown in the economy or a recession. Moreover, inflation may not necessarily need to have fallen back to the US Federal Reserve’s 2% target for the Fed to reduce interest rates. However, confidence that inflation will return to target does require at least for the economy to slow sufficiently. With economic growth at a 4% annualized pace over the second half of 2023 and not much sign of slowing further in 2024, there continues to be insufficient evidence that inflation will indeed fall back to target.

Why this time is different

In the rate-cutting cycles of ’84 and ’95, annual inflation never reached the heights it did in the past couple of years, peaking at 4.9% and 3.1%, respectively. By comparison, inflation during the pandemic peaked at 9% in June 2022, and the Fed’s tightening cycle through 2022 and 2023 has been much more aggressive.

Thus, scepticism surrounding the Fed’s ability to achieve a soft landing has been understandable. It’s important to note, however, that COVID-19 has muddied the waters on inflation. The pandemic resulted in a simultaneous large supply and demand shock, the likes we have not seen in recent history. It means we didn’t really know, and still don’t know how, exactly how inflation is going to respond after the pandemic. Will inflation just come down on its own as COVID-related supply dynamics sort themselves out, or do we need to see a further weakening in demand?

In June of last year, I argued that after a rapid easing in inflation, inflation could continue to hover above 3%. This is because inflation was not only a result of temporary supply constraints brought about by the pandemic but also because of strong demand. In other words, inflation would come down on its own as supply constraints eased, but there could be an element of inflation that would be more persistent unless we saw a more substantial slowing in demand.

Annual inflation initially fell rapidly, but it has failed to drop below 3% since falling to that level in June 2023. While we have seen demand and job growth moderate, both are still growing steadily.

No landing yet

Unfortunately, that means that we cannot yet conclude that a soft landing is inevitable, even though the odds of one have lifted since inflation peaked in mid-2022.

With inflation holding above 3% since June 2023, it appears increasingly likely that a further slowing in the economy will be necessary for inflation to reach the Fed’s 2% target. That does not necessarily mean the Fed would turn around and hike rates but could mean that rates will be on hold until later this year, and later than what financial markets are currently suggesting. Financial markets are pricing in around 80 basis points of cuts this year with the first cut beginning around June or July.

That might suggest that the sell-off in bonds (rebound in bond yields) since the beginning of the year has further to run. Higher for longer might also limit gains in share markets and risky assets, and prevent the US dollar from significant weakness. However, a turnaround from the recent risk-on trend in financial markets might require greater recession risk or a more serious consideration of another rate hike.

We have not yet landed. A soft-landing scenario remains possible. But a hard landing still cannot be ruled out.