Can Government Bonds Continue to Act as Defensive Investments?

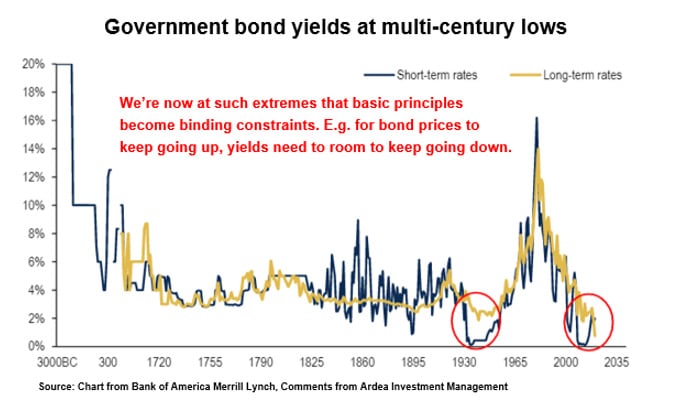

Government bond markets are now at the precipice of a paradigm shift. Unprecedented global fiscal stimulus. Extreme monetary policy experiments. Yields at multi-century lows.

In combination, these factors fundamentally change the risk vs. reward proposition of government bonds. So much so, they challenge conventional assumptions about how bonds should behave and the defensive role they are supposed to play in multi-asset investment portfolios.

Meanwhile, policymakers have the unenviable task of striking a very fine balance. Too little stimulus means a painfully severe recession. Too much risks loss of credibility on inflation control and government debt sustainability.

Faced with all this, it would be imprudent not to at least question whether government bonds are still the ‘safe haven’ they are assumed to be. To question whether interest rate duration is still a reliable hedge for equity risk.

At the risk of stretching metaphors too far, fiscal stimulus is now back in fashion and will remain so until the bond vigilantes (i.e. the fashion police) say, enough!

The term ‘bond vigilante’ was coined by former Yale economist Ed Yardeni in the 1980s to describe bond investors who push back on excessive government spending by demanding higher risk premia (i.e. higher yields) on government bonds. They may be poised to make a comeback.

The fiscal stimulus unleashed globally over the past since the start of the year is astounding, both in terms of its speed and its scale. This amount of government spending is rarely seen outside wartime, and it is coming on top of a decade worth of accumulated monetary easing.

While the last decade was dominated by monetary policy, 2020 will be remembered as the year fiscal stimulus became fashionable again.

Right now, investors are entirely focused on the near-term economic damage from virus disruptions, which means markets are applauding every new stimulus program being announced. However, we will eventually reach a tipping point where the consequences of all this policy stimulus will have to be weighed.

What does it mean for government finances, will bond investors start demanding more risk premium, will the bond vigilantes make a comeback?

Can bond markets handle so much new government bond issuance, will longer dated bond yields shoot higher or will central bank buying be enough to maintain the supply vs. demand balance?

At a time when monetary policy is already pushing new extremes, will so much fiscal stimulus cause longer term inflation expectations to shoot higher and what would that mean for the stability of currencies?

[Also read: Australian Government Sets New Bond Record]

No one can answer these questions with certainty, but it is a safe bet that bonds will behave very differently going forward than they have in the past, which in turn has important implications for portfolio construction and the traditional assumption that government bonds are a ‘safe haven’ asset.

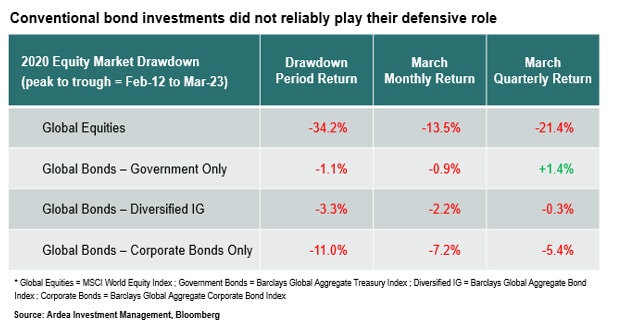

We’re already seeing these dynamics playing out as bonds failed to hedge equity risk reliably during the February / March global equity drawdown – one of the most violent on record.

This changing behaviour of bonds undermines the central assumption underpinning most multi-asset portfolio construction models i.e. that the interest rate duration inherent in government bonds will protect against equity losses.

Given the sheer size of equity market in March, conventional bond investments were supposed to provide decent protection. They did not.

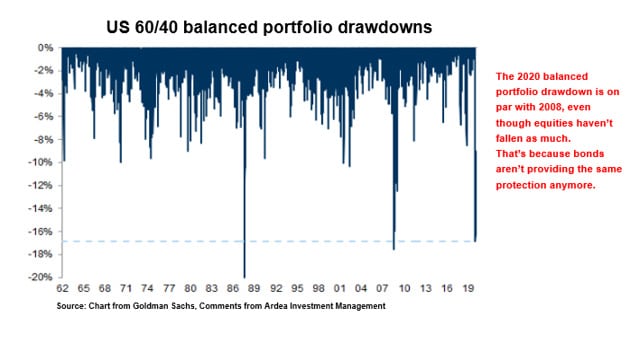

As Goldman Sachs points out, in relation to typical government bond / equity balanced portfolios:

“A 60/40 portfolio had one of the largest drawdowns since the 1960s this month. This was due to the sharp equity drawdown but also as there was less of a buffer and diversification from bonds.

… In addition to the sharper-than-normal equity correction, diversification in 60/40 portfolios has been less good. First, with bond yields at all-time lows now and close to the effective lower bound, there is little space for most DM bonds to buffer equity drawdowns. In other words, the beta of bonds to equities has declined, especially in Europe and Japan. But also equity-bond correlations turned positive in most markets”

– Goldman Sachs, ‘The 60/40 Drawdown and Multi-Asset Portfolio Risk’, Mar 2020

Given monetary policy has already gone ‘all in’ and given the avalanche of new government bond supply coming to fund all the promised fiscal stimulus, government bond markets now face the base case scenario of outsized price volatility relative to their meagre returns and the tail risk scenario of future inflation spikes imposing crushing losses on long duration bond exposures.

That is unless central banks everywhere can impose Japan-like control, but with the starting point of government bond yields now at multi-century lows, you are really not getting paid much to take that bet.

Why has fiscal policy taken over?

While monetary policy is still being deployed aggressively to fight the current crisis, its first order focus is not economic stimulus but rather, restoring liquidity and proper functioning to financial markets. That process began in mid-March, led by the US Federal Reserve (FED), and other central banks have since followed.

The unprecedented scale of central bank liquidity injections and bond buying programs (i.e. quantitative easing – QE) was first aimed at improving liquidity in core interest rate markets (i.e. high-quality government bonds and related interest rate derivatives) and then moved onto addressing more severely dysfunctional credit markets.

They started with core rate markets because, as we saw during the 2008 financial crisis (GFC), interest rate markets need to stabilise and function properly before any other market can. Core rate markets are the plumbing of the financial system, they are the risk-free benchmark from which everything else is priced. They need to function properly before anything else can stabilise.

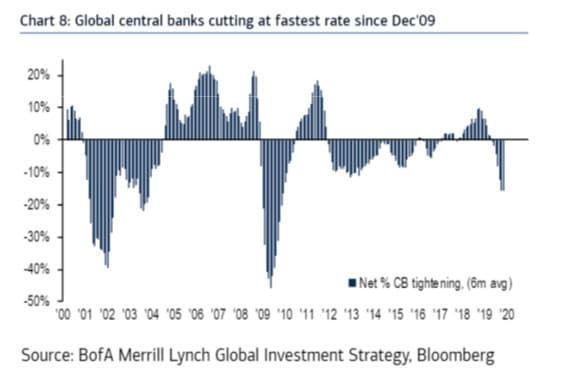

However, when it comes to the economic stimulus needed to soften the blow from virus disruptions, fiscal policy has taken over because monetary policy had already pretty much reached its limits.

We’ve noted before that ultra-loose monetary policy was like the central bank bar tab that was immediately topped up at the slightest sign of the asset price party waning.

In 2018, central banks led by the FED, tried to reign the party in by starting to normalise interest rates. The partygoers reacted badly, pushing equity markets into, what was at that time, the biggest drawdown since the GFC. Thus 2019 became the year in which financial markets bullied central banks into keeping the bar tab open and letting the party continue.

In fact, not only did they keep the party going, they ramped it up even more by returning to full scale stimulus mode. Led by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) push deeper into negative interest rates, central banks in 2019 were cutting rates at the fastest rate since the GFC.

The failure to build up an interest rate cushion, by materially raising rates in prior years when economic growth was OK, meant that by the time the virus hit in 2020, the central bank bar tab was already pretty much depleted from an economic stimulus perspective.

Even worse, it became increasingly apparent that the negative side effects of ultra-low rates were starting to outweigh any benefits. Much like the effects of alcohol transitioning from pleasant social lubrication to messy drunkenness, with drunken excess being an appropriate comparison for such incredible developments as ‘junk’ rated bonds trading with negative yields.

These dynamics were explained in the following article about Sweden’s decision to finally shut the central bank bar tab last year:

“This is also the most explicit signal yet of growing concerns in Europe about the collateral damage and unintended consequences of protracted and excessive reliance on unconventional monetary measures, particularly negative interest rates and large-scale purchases of securities.

The loud Riksbank message to other central banks is that being “the only game in town” for too long can make them not just ineffective but also counterproductive.

If Sweden can hold out as the monetary policy outlier in Europe — and it’s far from easy given the “small country” conditions — this could well be looked back at as the beginning of the end of a historic policy experiment, one that worked initially but was subsequently undermined by the failure of politicians to enable the much-needed pivot to a more comprehensive pro-growth policy response.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Sweden says enough is enough on negative rates’, Dec 2019

And in a similar vein from the Financial Times:

“It is the biggest monetary policy experiment of modern times. One that has divided economists, central bankers and politicians. But now that Sweden has called a halt to its five-year trial with negative interest rates the serious work has begun on looking at whether it worked.

Sweden’s Riksbank, the world’s oldest central bank, was the first to take its main repurchase rate — at which commercial banks can both borrow or deposit money — negative in early 2015, to fend off deflation, only returning to zero in December.

The end of the Swedish experiment is being watched with intense fascination, not just by those central banks that still have negative rates such as the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan, but also by authorities and economists worldwide pondering how to respond to the next downturn with limited ammunition to stimulate the economy.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Why Sweden ditched its negative rate experiment’, Feb 2020

In the post-GFC era, policymakers had become increasingly reliant on monetary stimulus as the policy tool of choice to mitigate economic growth risks, even as there was progressively growing doubt about its continuing efficacy. Making this point, the editorial board of the Financial Times noted the following in January this year:

“For four decades, monetary policy has been the dominant instrument of macroeconomic policy and central banks the queens of macroeconomic policy.

…Today, however, even unconventional monetary policy looks exhausted. Short-term central bank interest rates are close to zero in the eurozone and Japan and a mere 0.75 per cent in the UK. In the US, the Federal Reserve was unable to get rates above 2.5 per cent in the upswing and is now back down to 1.75 per cent.

… Room for action in response to a significant downturn is limited. Historically, the Fed has cut rates by as much as 5 percentage points in response to a recession. That would bring US rates to minus 3.25 per cent. This would only work if depositors could be charged for leaving money in banks.

… Yet there are deeper reasons for rediscovering fiscal policy. The most important is that its side-effects are less bad. Monetary policy works via expansion and contraction of credit, via shifts in asset prices, and via the quantity of a relevant monetary aggregate. The first has generated destabilising credit bubbles. The second can create significant economic distortions. Central banks have lost faith in the last.”

– Financial Times, ‘Active fiscal policy must be part of a new normal’, Jan 2020

So when the virus disruptions hit, there was no choice but for fiscal policy to step up … and it has done so in a huge way.