From Craig Brooke, KeyInvest CEO

Strictly speaking, private credit (or debt) is a sub-asset class of fixed income where companies borrow and investors lend. However, some of its characteristics align it more with alternative investments rather than fixed interest. However, is it now large enough to have formed its own asset class? To understand this better, it’s essential to look at the current investor interest in private credit.

It has been a recognised asset class for decades but gained significant traction after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) for two main reasons.

In the wake of the GFC, central banks took stern measures to strengthen commercial banks balance sheets, by backing their loans with more capital to absorb potential losses, especially loans to sectors such as commercial property development.

Consequently, banks became more focused on consumer loans for residential property, especially in Australia where APRA imposed stringent capital requirements. This shift led to intense competition for consumer home loans, as these attracted lower capital risk weights.

While mainstream banks have partially withdrawn from direct business and commercial property loans, they continue to support non-bank lenders through wholesale funding solutions.

These solutions involve warehouse structures with mezzanine layers that subordinate the bank’s funding, reducing the regulator’s applied credit risk weight and allowing indirect participation in commercial property loans. Private credit managers, through their own origination channels, assess and issue these loans, with many top managers in Australia using wholesale funding warehouses to support growth.

But the market still abhors a vacuum. Property developers need capital (as do SMEs), Australia is in dire need of more homes and private credit has quickly filled the gap, providing borrowers with flexible, tailored solutions for their funding. EY calculates the Australian private credit market has grown from $35 billion in 2016 to $109 billion by the end of 2022, a 21 per cent compounded annual growth rate. Then at the end of 2023 EY estimated the size of the private credit market in Australia ballooned to $188 billion.

Globally, the private data firm Preqin estimates this market will reach $US2.8 trillion ($4.3 trillion) by 2028, almost doubling the 2022 figure of $US1.5 trillion ($2.3 trillion).

Also read: Public and Private Credit: Where Investors Should Focus

That’s the demand side for private credit. For investors, private credit offers a winning quadrella – attractive yields (broadly ranging from 8-11 per cent depending on an investors’ risk profile), low volatility (largely uncorrelated to publicly listed assets – equity or debt), regular income (in 2022, when bond and share prices fell heavily, well-managed private credit funds continued to deliver regular income) and portfolio diversification.

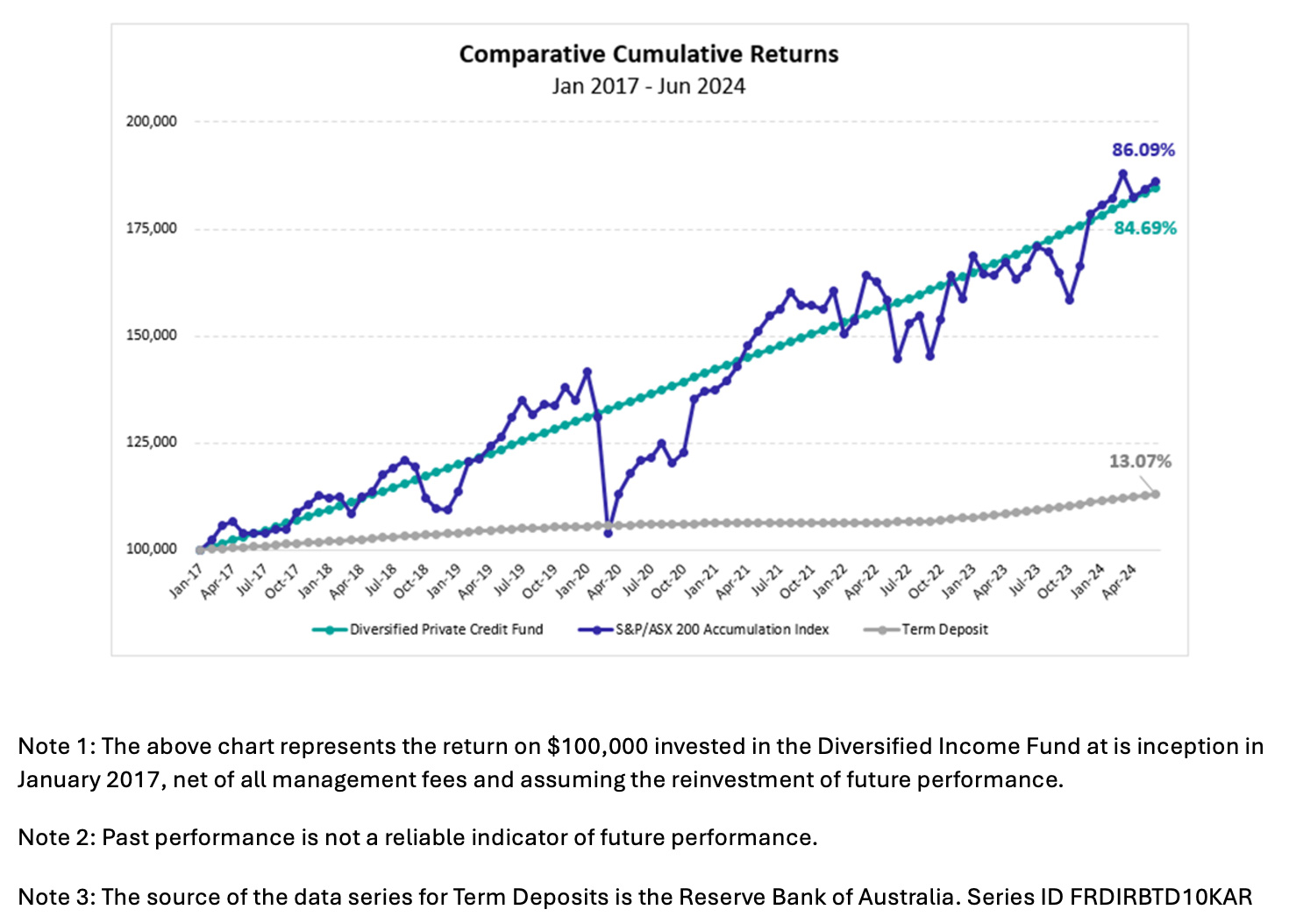

The below details a simple benchmarking of a 1st registered mortgage Private Credit Fund benched against the ASX Accumulation Index and Term Deposits, detailing the levels of equity and diversification for advisers and investors seeking stability, reliable income and capital preservation.

Unlike government and corporate bonds, this doesn’t require a large capital outlay and are easily understood by investors.

However, there are risks, including illiquidity, opacity, and loan defaults. Private credit investments typically have lock-up periods, limiting quick access to capital, and lack readily available market prices, complicating risk and return assessments.

A loan defaulting can see an investor lose some or all their capital. In addition, there are macroeconomic risks such as rising interest rates or a slowing economy, although it’s worth adding all investment asset classes are vulnerable to macro influences.

Majority of Australian private credit is secured at the top of the capital stack through a first registered mortgage and modest loan to valuation ratio, resulting in a level of security that investors have as backing as opposed to pure equity which can be wiped out in an instant.

So, how should private credit be classified?

Traditionally, it’s been given the “alternative” moniker. These are assets defined as any investment that falls outside the boundaries of long-only investments such as equities, property, and bonds. [Aside from private credit, it can include hedge funds, private equity, even art and vintage cars.]

But the growth of private credit in Australia and globally is raising the question of whether it should be considered part of a fixed income allocation or recognised as a stand-alone asset class, with the evidence increasingly suggesting it should be the latter.

At an institutional level, research conducted in January 2024 of 10 of the largest superannuation funds found that MySuper allocations to private credit ranged from 0.2 per cent to seven per cent, sometimes exceeding cash allocations, demonstrating the importance of private credit to those managing retirement savings.

Private credit is now appealing to high-net-worth investors, especially SMSFs in retirement phase seeking yield, family offices, and the retail market. The yields offered by private credit, especially when compared to the low returns from cash and term deposits a couple of years ago, are highly enticing. As of now, the yield on private credit generally ranges between four and seven per cent above the RBA cash rate, further evidence of private credit’s mainstream credentials.

But it’s the global trend that presents the strongest argument for giving private credit stand-alone status. So, while the private credit figure is approaching $200 billion in Australia, it’s what’s happening overseas, when coupled with Australia’s penchant for following in the footsteps of the US and European markets, that could see it grow exponentially in Australia.

Currently, private credit’s share of commercial lending in Australia is approaching 10 per cent. In Europe it’s nearly 50 per cent of the market, and in the US, it now comprises more than half the commercial loans written.

Considering the market grip that the Big Four banks have, those figures for the Europe and the US are unlikely to be replicated here. But even if private credit market only doubles in size – aided by the fact $4 trillion in superannuation assets need to find a home in risk-weighted sectors such as debt – it will deserve its own asset ranking, neither debt nor alternative.