In their most recent Insight, EMD on the bread line, Aviva Investors has outlined how soaring food prices and social unrest intertwine with countries’ fiscal positions and its impact on emerging market debt investors.

-

Rising food prices has increased risk of social unrest in emerging market countries globally

-

As Sri Lanka has shown, if governments have insufficient fiscal headroom to subsidise food, the danger is social unrest ensues

-

Several countries stand out consistently as being vulnerable to the kind of pressures which led to Sri Lanka defaulting

-

Most Asian nations have been supported so far by healthy supplies of rice, resulting in comparatively limited price rises

-

Angola, Nigeria, Ghana, Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, and Pakistan stand out consistently as being in danger.

Food prices, which were already at a ten-year high because of a series of poor global harvests, skyrocketed this spring as the war in Ukraine cut off supplies from the world’s biggest exporter of sunflower oil and a major producer of cereals such as maize and wheat.

Across emerging markets, the rate at which food prices are rising varies significantly. In some countries it is running at less than five per cent. Perhaps most notably, comparatively stable rice prices have helped suppress food inflation across much of Asia, at least for now. Countries with pegged or heavily managed exchange rates, for example some Middle East states as well as Ecuador and Gabon, have also been less impacted.

By contrast, Angola, Ghana, Columbia, Sri Lanka and Egypt are all currently experiencing food inflation of 25 per cent or more.

Soaring food prices are especially problematic for poorer countries where food accounts for far more of the average household shopping basket than it does in richer nations. Often the biggest single constituent of consumer price indices, it typically accounts for around 25 per cent of household outlays.

Worsening terms of trade

Although rising food prices could be of overall benefit to some countries, such as Uruguay, which is a major food exporter, they are the exception. Analysis by Goldman Sachs shows that so far this year, the food terms of trade – the change in the price of food exports / the change in the price of food imports, weighted according to exports’ and imports’ respective shares of GDP – have worsened for 80 per cent of emerging market countries. In other words, the economic benefit to these countries of a rise in the value of their food exports is being outweighed by the rising cost of imported foodstuffs.

Rising social unrest

High food inflation is an issue in its own right. However, it becomes especially concerning when it risks stoking social unrest and political upheaval.

Also read: The World Has Changed: Implications For Bond Market Investors

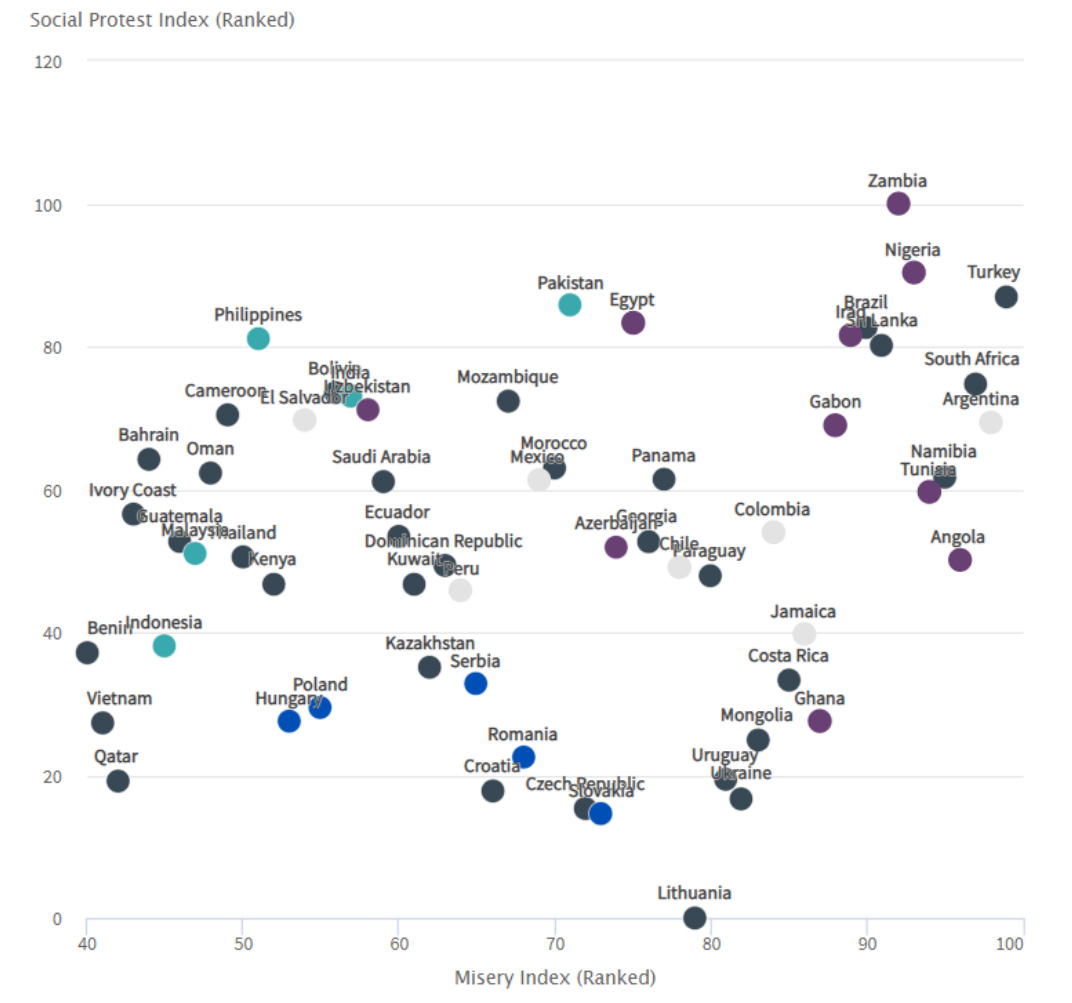

Aviva Investors have constructed an index that tries to approximate individual countries’ vulnerability to the threat of rising social unrest, capturing a nation’s social and governance characteristics.

This index comprises six different factors: wealth inequality, changes in per capita income and labour force participation rates, which attempt to capture living standards. In terms of governance considerations, Aviva Investors’ accounts for levels of corruption and political stability. Finally, the firm includes the level of economic freedom, which some studies suggest correlates strongly with happier societies. The results are shown below.

The danger of soaring food prices leading to social unrest and rising risk of default is increasingly being appreciated by markets, and among the factors contributing to the current sell-off in emerging-market debt. Sri Lanka is unlikely to be the last to default. The IMF has opened programme talks with Egypt and Tunisia, both big importers of wheat from Russia and Ukraine, and with Pakistan, which has imposed power cuts because of the high cost of imported energy. Turkey is battling 70 per cent inflation and the risk of a balance of payments crisis is building.

By considering countries’ vulnerability to the kind of pressures which led to Sri Lanka defaulting, Aviva Investors’ believes it is possible to glean useful insight into the location of other potential fault lines within the emerging sovereign debt universe.

Several countries – namely Angola, Nigeria, Ghana, Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, and Pakistan – stand out consistently as being in danger, even when considering the risks from a variety of different angles. This does not mean any of these countries will default in the near term, but it does suggest extra emphasis must be placed on understanding and assessing any building social pressures, and how each government is likely to respond.

As for the bulk of Asian nations, they have so far been helped by healthy supplies of rice, resulting in comparatively limited price rises. However, should recent trends persist, there is a growing likelihood people will begin substituting rice for wheat. That would put upward pressure on prices, especially if countries such as Thailand were to respond by restricting exports. The Philippines and India, with high levels of malnutrition and a high risk of social unrest, could also find themselves in difficulty.

As the Arab Spring of the early 2010s showed, rising food prices have the potential to spark widespread unrest and political upheaval. Although underlying pressures were building up for years, it was only when the price of bread went up and people could not afford to buy it that they took to the streets.

Given the pace at which food prices have been rising, emerging-market countries look to be at growing risk of social unrest. The concern is greatest for those countries where public finances are under strain or likely to deteriorate. Investors should keep a close eye on events.