It’s not hard to see why investors and asset allocators are in a dichotomy over when/how/why to consider upping allocations or reallocating to fixed income. Unless a bond market participant – and frankly even then dispersion of view is wide – trying to fathom clear rationale against a noisy macroeconomic and geopolitical backdrop is tricky. We look to sage words attributed to the other infamous Donald Rumsfeld in his 2002 answer to a question on Iraqi WMD:

“…there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

This same logic is infinitely applicable to the world of investing; there’s some stuff we can observe and assess with a fair degree of conviction, some stuff we try to assess but with such variability of outcome conviction would be unreliable, and then there’s the stuff we have no idea might have an impact on our portfolios. As a starting point it’s therefore sensible to try and bracket the information flow in this way; base your highest conviction views on what you have a good analytical grasp of, take a measured position against the forecast variability of trickier outcomes, and try and stay clear of risks that are impossible to model with any degree of surety.

So first, what do we know about what has happened of late to have an effect on global fixed income markets?

Also read: How Much Public Debt Is Too Much?

Unwinding of the stimulatory cheap money gift bestowed on us all by countless central banks eager to prop up economic activity as we emerged blinking from the fug of a global pandemic. Check.

The ‘Great Yield Reset’ as the same central banks in their then efforts to drive down a rampant inflationary environment as supply chain disruption and pent-up spending propensity clashed. Check (well, mostly, as it turns out this inflation beast is proving a little trickier to tame than anticipated…).

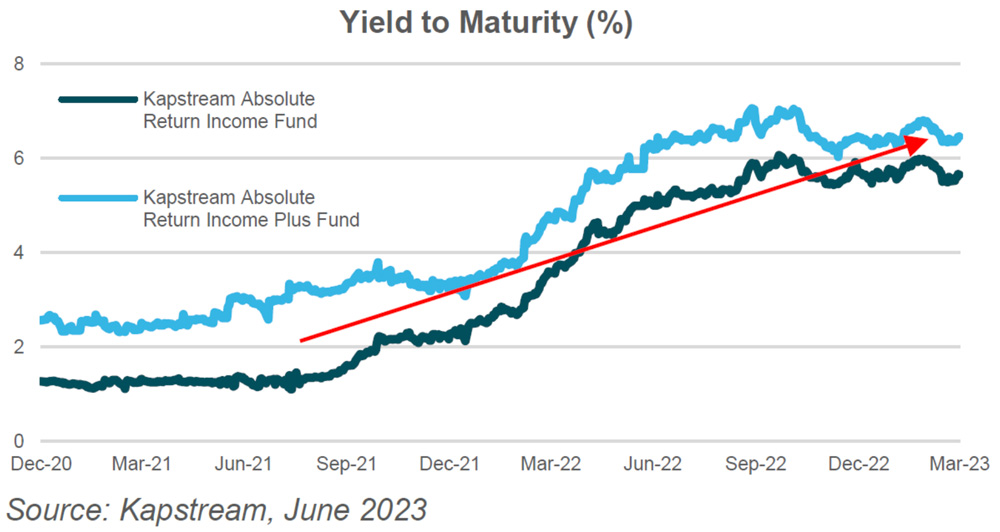

Cash is back to ~4% and still climbing, most welcome level if you’re a depositor. A little less appealing for borrowers, but c’est la vie. Bonds, essentially just another form of borrowing for companies and governments and ultimately pegged to those same cash levels, are again offering highly attractive yields, with spreads above the risk free rate varying with their rated ability to repay their debt through time. Today, a predominantly investment grade portfolio of even very short-dated bonds provides investors with a yield to maturity of between 6-7% (a significant change compared to 1-2% just a year or so back, see chart below). And, worth mentioning, not massively different to the equity dividend yields on offer from comparable corporates (“yeah but what about capital growth?”, you say… we’ll get back to that).

For the first time in several years, investors are no longer forced into low grade bonds nor illiquid bonds in order to maintain an appealing coupon yield. While high yield and private debt will always retain an important role in portfolios and continue to provide a valuable source of return diversification, it’s no longer the only place to place capital in order to secure a worthwhile return.

We could just stop here. However that risks ignoring some fairly weighty impacts – some of the known and unknown unknowns – that cannot be brushed under the carpet. Despite the return attraction of a risen yield environment, this is far from being a set and forget or ‘invest in May and go away’ situation. Significant uncertainties with the ability to materially upset an otherwise rosy outlook persist.

First, this niggling inflation issue. Until more recently, it’s been coming down for decades. Central banks moved to targeting inflation. Labour market reform de-centralised the wage negotiation process and improved labour market flexibility. Oil prices also did not repeat the frequency of the spikes seen in the ‘70s. All of these factors helped reduce inflation in a trend sense. And bond yields followed, helped lower still by interventionist ZIRP style tactics as central banks attempted CPR on flatlining economies lunging from lock down to lock down. But that, as they say, is history.

With all the noise of the last 2-3 years, the implications of the end of the long-run trend decline in inflation and its positively correlated relationship with bond yields has not yet been fully appreciated. As (inflation and) yields fell, the price of those bonds increased, for some time masking the ultra-low coupon carry in terms of running yield, until yields began to approach zero. Long-run historical returns for fixed income funds were therefore almost invisibly boosted by this downtrend. The longer the duration of the portfolio, the more benefit it received from that trend decline in yields, of between a quarter and a half per cent per annum.

Now moving to a very different environment, the impact of bond yields trending sideways rather than down is yet to be understood. Make no mistake this is coming. The returns for fixed income up until ~2020 were still benefiting from higher yields and the downtrend up until that point. If the long run trend decline in yields ends globally as it has in the US, then investors must accept that that component return from bond yield downward movement will play a far more modest role going forwards. Longer-duration portfolios will be hit the hardest, where the benefit from a trend decline in yields is greater. In a world where yields trend sideways, the total return from short-duration funds and long-duration funds will be much closer (than in the past downward trending environment), and worse still the long duration funds will exhibit much greater volatility within the cycle as central banks adjust rates up and down. In other words, the efficiency of long-duration funds will be much lower as the return-to-volatility ratio will decline markedly.

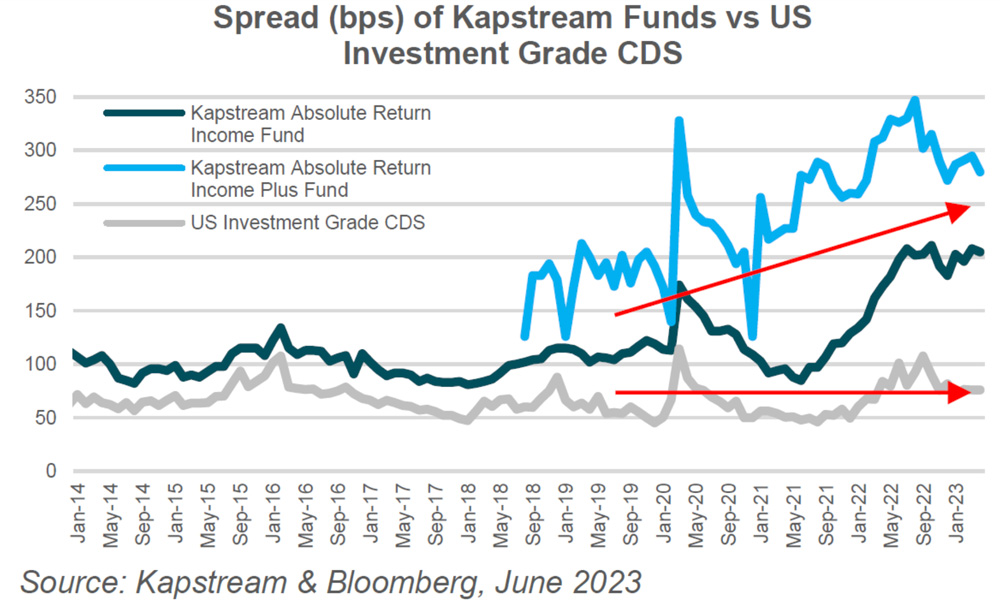

This also means that fixed income managers will need to factor in how such a secular shift affects sources of return. While in Kapstreams case as a low duration manager that doesn’t rely to any extent on interest rate change for return generation – and this is not a cyclical view but a philosophical one based on the low information ratio characteristic of duration as a structural return driver – one way we have sought to offset this is by increasing the credit spread in portfolios (see chart below), but in a way that does not increase the sensitivity of the portfolio to spread movements, nor take on materially higher default risk. Ta daaa! Sound too good to be true? It’s just about moving to a more efficient point in where you invest – and again shorter-dated assets are the way to go.

To explain, investing in A rated assets with a duration of 7 years has far more price volatility than a BBB rated asset of 3 years duration through the cycle. Thus the impact from having more duration (and therefore sensitivity to spread movements) is far more impactful on the price than the relative spread movements of BBB rated versus A rated bonds over the cycle. The probability of default is also not significantly different, with the historical default rate1 for an A rated asset over 7 years at 1.41%, a lot higher than a BBB rated asset over 3 years at 0.66% (put simply, one can gain greater comfort that a bond issuer will be able to make good on its debt commitments over a shorter time frame than longer, and therefore hold higher conviction). When this is converted into an expected loss figure per annum, it comes out to being roughly the same. This supports the case that increasing the exposure to shorter-dated, but slightly lower-rated assets is both more efficient, and can offer more coupon carry in a long-run average sense over the cycle, without comprising on capital preservation goals. Have your cake and eat it time.

To some of the more apparent unknowns, the lagged impact of rate hikes over 2022 is still yet to be fully reflected in the economy and economic data. The extent of the economic decline and its flow through to corporate earnings and risk sentiment remains a key reason to remain well insulated from these uncertain impacts and to be cautiously positioned. Equally, blunt or simple ‘beta’ allocations will be risky, as instances such as SVB and Signature and Credit Suisse will almost inevitably be repeated as financials and corporates themselves grapple with the same higher borrowing costs challenge that consumers face. Let’s not forget that there were six months between the collapse of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers – at the time generally considered to be isolated events – prior to the GFC.

So plenty still to ‘fan the flames’ of a looming recession. Risk markets are adept at shrugging off fears of market malaise until right in the eye of the storm. Historic data tells us that most recessions are, from an equity markets perspective, characterised by a drawdown of ~30-35%. At the time of writing, equity markets are less than half of that off their peak. That suggests we should expect another leg down of some magnitude (and if you subscribe to that view, there’s your reference to the mid-term potential for capital loss from your equity portfolio). Credit spreads are not immune to that, and certain expectation has to be factored into how you allocate, for example maintaining very short spread duration, adding protection, and at the very least holding an overweight cash position ready to deploy into wider spread opportunities when they come.

Pulling this all together, there is no doubt that the ‘wait to weight’ is more emotionally driven and careful allocation today to fixed income may yield decade high return opportunities given the positive backdrop of a far more attractive yield environment. In the same breath participants should at least temper their expectation of material return coming from interest rate contribution (at least from an acceptable risk-adjusted perspective) and cautiously limit exposures accordingly, given the end of the trend decline in yields, as well as insulating themselves from the myriad of unknowns. Lower duration products and notably those skewed towards absolute return outcomes will have an even higher information ratio compared with conventional benchmark oriented fixed income strategies (carrying longer duration) than they have in the past. Active management to try and avoid the SVB and Credit Suisse type ‘banana skins’ – both those you know are there and those you don’t – will also be of increased relative importance. Is your fixed income exposure calibrated to this new paradigm?