By Alan Siow, co-head of emerging market corporate debt, Ninety One

The new regime

The shift to a new macroeconomic regime is among factors that have redrawn the fixed income investment landscape in the past few years. Major economies like the US are only just getting to grips with inflation – with rates set to remain higher for longer than many had hoped. They also face the daunting prospect of returning fiscal deficits to a post-pandemic sustainable path.

Add to that a proliferation of election-related uncertainty and increasing divergence across global economies, and old labels used by asset allocators no longer seem useful or fitting. This is particularly the case for ‘emerging markets,’ a label synonymous with higher volatility, lower perceived credit quality, and greater political uncertainty.

In recent years, there has been a ‘blurring of lines’ between developed and emerging market (EM) debt. Developments, such as proactive rate cutting that have underpinned a strengthening of EM fundamentals, have fed through into resilient sovereign debt market performance. Meanwhile, shifts in the developed market universe have resulted in a much more volatile fixed income market regime, with possibly the greatest political for investors yet to arrive from the looming US election.

While for the macro economy, inflation finally seems to be trending down in the US, many EM central banks are further ahead in their rate-cutting cycles. This, together with fundamentals that are generally on a positive trajectory, puts EM economies at an advantage.

Firmer foundations for EM corporate credit issuers

The fundamental improvements seen in EM economies naturally provide firmer foundations for the companies operating in them – and for the debt they issue. But that’s only part of the story.

The world order is undergoing a significant shift. The unipolar dominance of the past, characterised by the United States as the sole superpower, is transitioning to a multipolar world marked by various centres of economic, political, and military influence. Power shifts, by their nature, create both volatility and opportunity.

Countries that diversify their economies, build strong regional alliances, and can navigate between different global powers are likely to benefit.

Market-leading global companies with prudent management

An often-overlooked fact is that emerging markets are home to many market-leading companies, with a global footprint and geographically diverse revenue sources. Familiar brand names owned by EM companies include Samsung, Volvo, GE Appliances and Jaguar Land Rover.

Additionally, EM companies typically have very low leverage. These companies are familiar with volatility and have historically experienced periods when they struggled to finance themselves with longer-term debt. As a result, their short-term debt is higher as a percentage than it is in DM companies, which has led to a culture of retaining cash while containing leverage. This has been particularly evident since the COVID crisis, as many companies have pared back their expansion and capital expenditure, leaving them with healthy cash balances and strong buffers. The contrast with many developed market companies is stark.

A look behind the labels

While the case for including EM credit alongside DM allocations in portfolios is strong, pre-existing perceptions can be hard to shift. In keeping an informed and up-to-date view; key metrics of large, diverse and maturing asset class of EM credit are shared below:

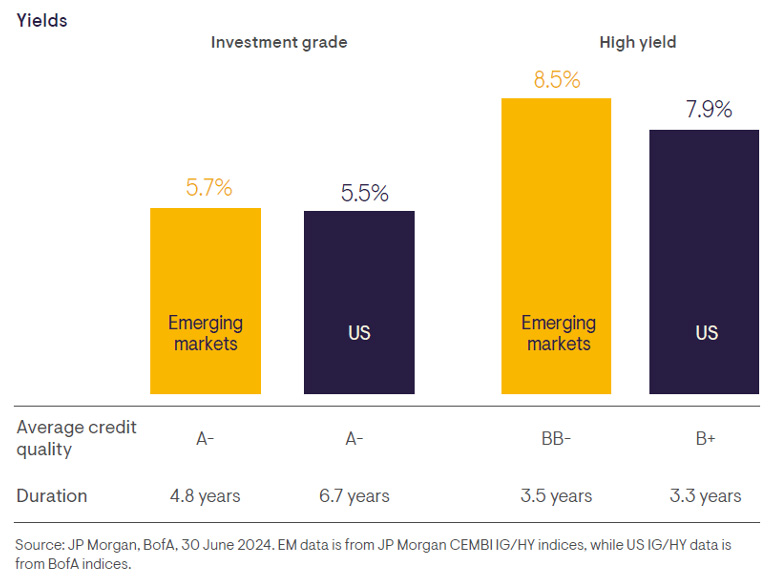

EM corporate credit offers comparable or superior yields, for similar credit quality and duration

Not only is the EM asset class a globally diverse universe that spans continents, in many ways, EM and DM/US credit markets are alike. In some respects, EM credits have more favourable characteristics. A look at the key characteristics of the asset class today and how it stacks up suggests it can play a useful role in a broader credit/growth fixed income allocation.