This article was part of an Ardea Investment Management paper title ‘Five Key Questions on Duration’, published on 25 July 2022. It helps investors assess whether bond yields provide adequate returns and uses 10-year government bond yield as an example.

The fixed income market is currently facing somewhat binary tail risks between recession and prolonged high inflation, or perhaps both together.

While declining bond yields would benefit investors initially, at the same time higher inflation and lower ongoing returns from lowered yields are not a favourable combination for long-term returns.

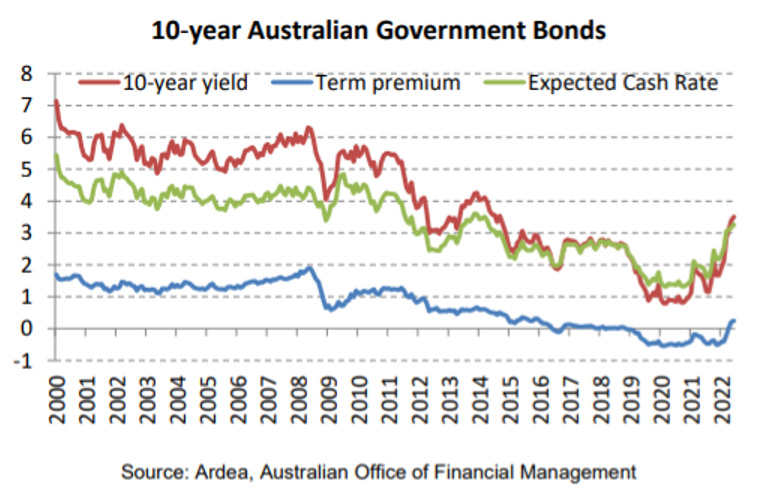

Given this challenging outlook, it is reasonable to assess whether bond yields provide adequate compensation to investors for this uncertainty. One long-standing approach to this question is to assess the term risk premium on offer in the government bond market.

The term risk premium aims to capture the return or yield on offer from government bonds, over and above the expected return from holding cash for an equivalent period to the life of a government bond.

For example, at current 10y government yields in Australia of 3.5%, this might translate to a term premium of 0.50% over the cash rate if the cash rate were to average 3% over the same 10y period. If however the cash rate were to average 2.5%, this would equate to a term risk premium of 1% on a 10y government bond yielding 3.5%.

Also read: S&P Default Rate Study

While there are many challenges in accurately measuring the term risk premium, given it can’t be observed directly, this framework provides us with a useful lens to compare current bond yields to historical levels. What we find is that when cash rate expectations are higher, the term risk premium is higher too. This produces bond yields that rise by more than just the increase in cash rate expectations alone.

This perspective can help investors form expectations about whether fixed income offers appropriate compensation for risk at given yield levels, and how this relates to cash rate expectations.

For example, taking the view that inflation in Australia averages 2.5% over the long term, a long-term cash rate of 2.5% would represent a real cash rate of zero. If one took the view that Australia should be able to deliver positive real cash rates over the long term, average inflation of 2.5% plus a positive real cash rate of 0.5% would translate to a long-term nominal cash rate of 3%. Current bond yields of 3.5% would provide only a 0.50% term risk premium above this number, thus providing compensation that is perhaps adequate, but not generous, and not comparable to longer term risk premium averages of around 1-2%.

The 10-year bond yield, the expected cash rate for 10 years, and the resulting difference which is the term risk premium are shown below. While there are numerous statistical and methodological limitations to this approach, it provides a further reference point in assessing the degree of comfort provided by current bond yields.

Australian 10-year yield decomposed