Franklin Templeton Fixed Income CIO Sonal Desai disagrees with the Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) choice of a larger 50 basis points (bps) instead of a more moderate 25 bps.

“But I agree with most of the underlying assessment of the economy that Fed Chairman Jerome Powell laid out. The latter, I believe, is going to prove key to what lies ahead for policy rates and market moves,” she noted.

Prior to the meeting, those advocating for a 50-bp cut brought two arguments: First, that at 5.25%–5.50%, the policy rate was far above its equilibrium level. Second, signs of a weakening economy—in particular the rising unemployment rate—called for the Fed to take meaningful steps to avert a recession. Both arguments were flawed, in my view, which is why I would have preferred a more prudent 25-bp cut.

Given the decision to cut by 50 bps, Powell’s top concern in the press conference was to dispel the idea that the Fed was seriously concerned about a possible recession. He repeated over and over again that the US economy is strong and that the labor market is still at or even above full employment. He said the Fed now sees risks to inflation and employment as balanced but added that he does not see any signs that currently flag a risk of recession.

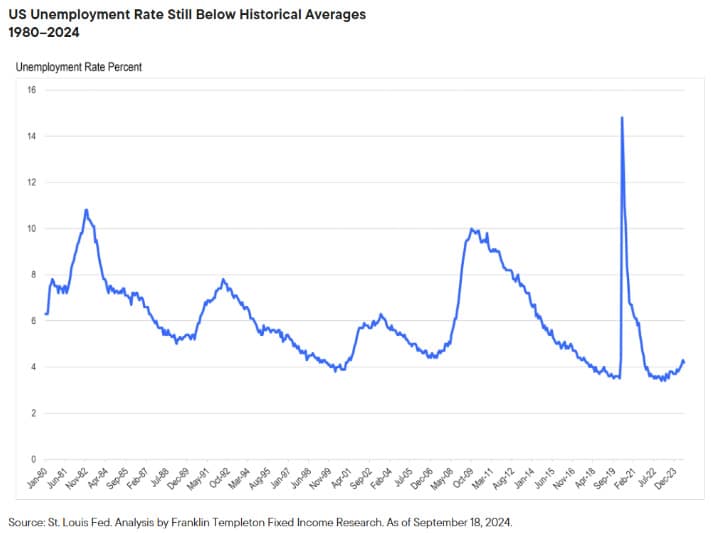

I could not agree more. Let’s start with the labor market. Yes, the unemployment rate has risen to 4.2% this August from a low of 3.4% in April last year. But that 3.4% was the lowest rate we had seen in about 60 years. Between 1990 and 2007 (the eve of the global financial crisis [GFC]), the unemployment rate averaged 5.4%, and the natural unemployment rate today probably sits somewhere in the 4.5%–5.0% range. So the labor market is just gradually getting back into balance from overly tight conditions. Responding to a question, Powell gave a detailed and data-rich assessment of what he also sees as a very solid labor market. The newly released Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) shows the Fed expects the unemployment rate to stabilize around current levels for the next three years.

Other recent economic indicators also look very healthy; retail sales remained resilient and industrial production rebounded strongly in August, leading the Atlanta Fed to raise its estimate of third quarter growth to 3% annualized. This is hardly an economy crying out for monetary stimulus. Powell’s assessment? “The economy is in strong shape, and we want to keep it there.”

Although Powell did not mention it, I would add that persistently loose fiscal policy will also give continued support to the economy over the coming years—something I have highlighted several times before. Both presidential candidates have put forward proposals that would lead to a significant increase in the fiscal deficit going forward.

Also read: Fed’s 50bps Cut Kickstarts Recalibration

Powell also acknowledged that inflation is not at target yet, though it’s come a lot closer, and the Fed now has much greater confidence that price growth will continue to decelerate to 2%.

Coming into the press conference, Powell also knew that a 50-bp cut might supercharge market expectations of further monetary easing. He poured buckets of cold water on the market’s enthusiasm, stressing that “I don’t think anyone should look at this [50-bp rate cut] and say this is the new pace [of monetary easing]” He stressed that the Fed is now looking at a gradual normalization of rates, and he pointed to the “dots,” where the median implies another two cuts by 25 bps this year (in line with my expectations and bringing the end-2024 fed funds to 4.4%) and an additional 100 bps in cuts over the course of 2025 (to 3.4%).

This brings me to the second crucial issue: How far are we really from the neutral fed funds rate?

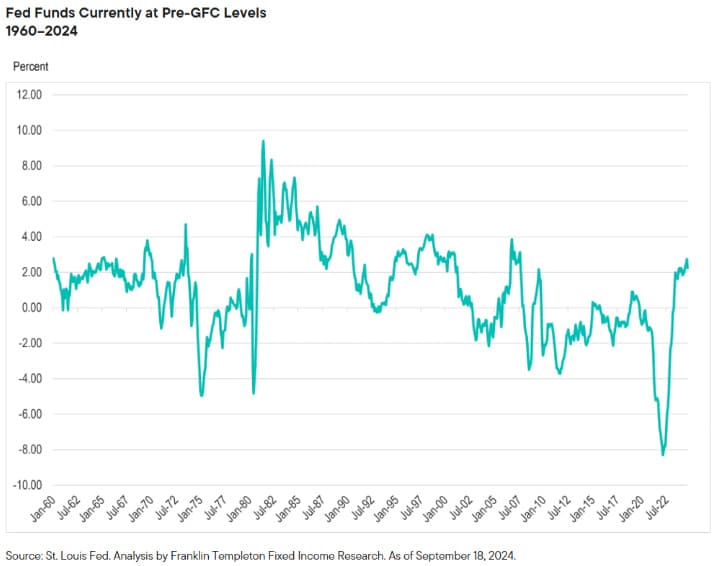

Taking a simple measure of the real fed funds rate, defined as the nominal fed funds minus the current inflation rate (which is now not too far from the future expected inflation rate) shows that monetary policy is tight, but not exceptionally so, from a historical perspective.

In fact, what jumps out from the chart is not how high the real policy rate is now, but how abnormally low it’s been since after the GFC. I have been arguing for some time that the period between the GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic was a historical aberration, and that a better reference point for where real fed funds should be is the long-term average prior to the GFC. That suggests a real policy rate close to 2%, not that far from current levels.

A quick look at financial conditions also confirms that monetary policy is not that tight (even prior to the September rate cut): (i) equity markets are close to all-time highs; (ii) credit remains abundant; and (iii) spreads on risky assets, from loans to high-yield credits, are tight. The last point, incidentally, also tells me that financial markets are not actually worried about a possible recession—the pricing of risky assets is simply inconsistent with an outlook of shrinking activity and rising bankruptcies.

In the press conference, for the first time that I can remember, Powell cautioned that his “sense” is that we are not going back to the ultra-low interest rates of 2008-2022, because the neutral rate is now significantly higher than it was back then. Where is the neutral rate now? Taking the near-2% pre-GFC long term average of the real policy rate I mentioned above, I estimate that, at the end of this easing cycle, fed funds should settle at a neutral rate of 3.75%-4.0%. The Fed (based on the median dot) currently envisions lowering the policy rate to 3.4% by the end of next year, and to about 3% at the end of the easing cycle. I would note that the Fed’s estimate of the neutral rate has been gradually inching up over the past year or so—probably acknowledging the economy’s resilience to the rate hikes—and might well rise further. By contrast, markets expect fed funds rate to fall to 2.75% already by the end of next year.

On balance therefore, Powell managed to deliver a 50-bp cut that was not particularly dovish. I can live with that. Markets, however, were a little disappointed, with 10-year US Treasuries selling off in the immediate aftermath of the press conference, when usually they have tended to rally as Powell’s press conferences often conveyed a dovish signal.

That means that for the Fed, the hard part lies ahead. Past experience suggests that financial markets will keep pushing for more easing than the Fed plans to deliver, especially as a number of investors still expect rates to revert to the extremely low post-GFC levels. Powell has his job cut out for him. The Fed has regained an important measure of anti-inflation credibility, but the “Fed put” enjoys a longstanding track record with investors.

I expect we will see several rounds of markets getting over-excited in response to any weakness in economic data, increasing the potential for subsequent disappointments, as we converge in fits and starts back to the pre-GFC norms.