-

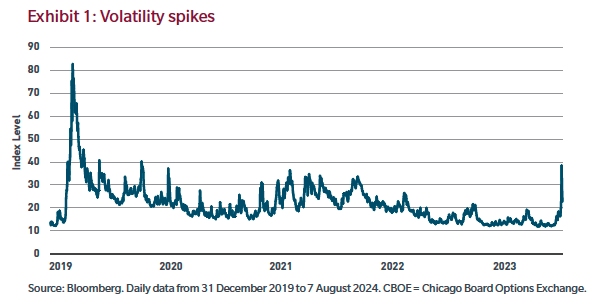

The VIX1 is signaling uncertainty is on the rise.

-

In our view, while recent earnings reports look fine, on closer inspection, companies report stress below the surface and concerns are growing that AI-related capex may have gotten ahead of itself.

-

Investors face the challenge of adjusting from a financialized post-global financial crisis paradigm to a new, higher-cost, higher-volatility one.

The VIX goes parabolic

In recent days, the Cboe Volatility Index, better known as the VIX, has reached heights not seen since the early days of the March 2020 COVID lockdown.

Typically, in life, but certainly in financial markets, the path from certainty to uncertainty is rarely slow and orderly but is instead abrupt. Why?

Probably like yours, my inbox has been littered with explanations ranging from rising US recession risks to the unwinding of a yen-funded carry trade to the potential for excesses in spending on infrastructure for artificial intelligence. While each were contributors, and I will offer some context, investors may not be internalizing the more important signal the VIX may be sending.

Pieces of the puzzle

While aggregate earnings reports have been fine, on closer inspection, comments from management teams point toward increasing strains across industries such as consumer cyclicals, basic materials, energy and capital goods, among others. This isn’t too surprising given that the cost of non-discretionary goods such as food and shelter remain elevated, forcing households to make substitutions elsewhere. These concerns were reinforced by weaker-than-expected manufacturing and employment data.

Not unlike households, budgets in the corporate world tend to be fixed and adjusted annually. The race to incorporate artificial intelligence into enterprises has cannibalized technology spend elsewhere, and AI is a potential threat to many software offerings. This has become evident over the past few months as at-risk software companies have missed earnings estimates or provided softer-than- expected guidance.

Also read: Implications From Market Dislocations

Speaking of AI, the spending by hyperscalers (giant providers of cloud computing services) to build out AI infrastructure has been massive and the projections for the future are even larger. Of course, the direct beneficiaries of this spending are companies across the infrastructure ecosystem, such as providers of chips, servers, electrical equipment, power components and the like. As noted earlier, while the shift in corporate wallet-share from software and other IT services to AI was fast, instituting real change to business processes takes time. Meaning, the tangible uptake of AI by enterprises has not matched the massive capital spending by the hyperscalers. We believe that while these investments will likely prove worthwhile in the years to come, that doesn’t mean there isn’t the risk of overbuilding or the risk of a slowdown in capital investment that challenges the revenue and profit assumptions for AI supply chain beneficiaries. It’s worth noting that history shows that when new technologies are introduced, the infrastructure associated with that technology is typically overbuilt. I highlighted this risk last December in How the Capital Cycle Could Impact 2024.

But I think these are only pieces in a much larger puzzle.

What volatility may really be signaling about the puzzle

Capitalism is the distribution of resources away from where they’re needed least to where they’re needed most. To function properly, providers of capital must be compensated for time. In the absence of compensation, market signals become blunted and malinvestments accrue.

Many seem to have forgotten that the world just recently exited a multi-year period of artificially suppressed interest rates that culminated in a 5,000 year low in borrowing costs.

Louis Gave of Gavekal Research recently cited a quote from John Mill’s 1867 paper on credit cycles and market panics: “Panics do not destroy capital. They merely reveal that extent for which it has been prematurely destroyed by its betrayal into hopelessly unproductive works.”

A decade of zero interest rates and quantitative easing drove a multi-year period of debt-financed acquisitions, dividend increases and stock buybacks. At the same time, offshoring drove down capital intensity and labor costs. These factors led to all-time high profit margins. But those trends have slowed, if not reversed.

Financial asset prices represent probabilities for future cash flows and non-linear spikes in volatility have tended to occur when investors were confronted with new information that upended prior cash flow assumptions. However, we feel the “new information,” such as the pieces of the puzzle described above, are being downplayed by strategists and talking heads.

Perhaps they’re right. Disorder is order that is misunderstood. What if the real signal isn’t acute profit stress but something chronic resulting from a new paradigm of normalized costs against a backdrop of weakening growth?

In such an environment, we believe we should see more, not less, volatility. As such, security selection, specifically avoiding assets tethered to “unproductive works” and unrealistic cash flow probabilities, could prove an apt investment approach.