A renewed US-China trade war under a potential second Trump presidency could disrupt global growth, financial markets and supply chains through aggressive tariff measures against China and other trading partners, according to Western Asset, a leading global fixed income investment manager and part of Franklin Templeton.

Robert Abad, product specialist at Western Asset, says: “The US presidential race is still in its early stages, but talk of another global trade war is picking up steam. Donald Trump, the presumed Republican nominee, has been increasingly vocal about his intentions for aggressive trade measures if he secures victory in November 2024. Whether this is mere campaign bluster or a firm policy stance is yet to be determined.

“However, the possibility of another intense trade dispute between the US and China is beginning to unsettle certain global investors, and it’s easy to see why.”

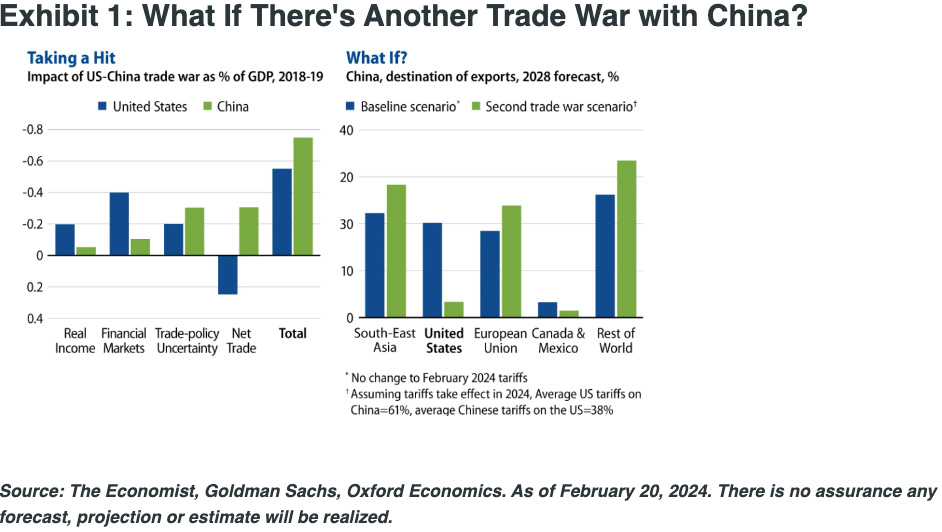

During its peak in 2018-2019, the US-China trade war had a substantial impact on China’s quarterly gross domestic product (GDP), reducing it by as much as 0.8% (Exhibit 1). Although the net trade effect favored the US over China, the conflict disrupted financial markets in both countries and contributed to policy uncertainty, which in turn restrained income generation and business spending.1”

Abad says: “Another trade war at this juncture in the global macroeconomic cycle, especially one that significantly affects China’s growth prospects, could reignite fears of a global recession and, coincidentally, raise concerns about the potential inflationary consequences of higher tariffs.”

Also read: The Late-cycle Environment Continues To Play Out

According to a recent story in the Washington Post,2 Trump and his advisors are contemplating a three-pronged tariff strategy that could include:

- Introduction of a new US “price of admission” that entails implementing a universal baseline tariff of 10% on nearly all imported goods. Such a move would mark an estimated ninefold increase in the quantity of goods subject to tariffs compared to Trump’s first term.3

- Heightened punitive measures against China involving a revocation of China’s Most Favored Nation status (or Permanent Normal Trade Relations [PNTR] in US law), initiating a four-year plan to phase out all Chinese imports of essential goods—spanning electronics, steel and pharmaceuticals—and surprisingly, imposing tariffs as high as 60% on all imports from China.4

- Implementation of “reciprocal” tariffs entails applying tariffs or a special value-added tax that matches the tariffs imposed by other countries on exports from the US.

He says: “All of these proposals potentially elicit swift and proportionate countermeasures, particularly from China, leading to substantial disruptions in the global economy that could exceed the impact of the trade war during Trump’s initial term.5”

In 2018, global financial markets were blindsided by the Trump Administration’s decision to launch a trade war with China and multiple US allies. The impact on the US equity market was severe as it experienced a $1.7 trillion loss in market value at the height of US-China trade tensions in mid-2019.6 During this period, developed market (DM) government bond yields declined sharply as investors began considering the possibility of major central banks implementing more aggressive rate cuts to counteract global growth risks. For example, the yields of 10-year German bunds and UK gilts dropped by 49 basis points (bps) and 54 bps, respectively, following the lead of US Treasuries (USTs), which fell by 87 bps during 2019. Furthermore, concerns about a global currency war emerged when the Chinese yuan depreciated beyond the psychologically significant 7 per dollar mark—a level not seen since the 2008 global financial crisis—precipitating a selloff in emerging market (EM) equity and currency markets.7

Current market valuations may already account for the possibility of Trump not securing re-election and his confrontational trade policies not coming to fruition. However, market sentiment can swiftly shift in the lead-up to the election if the likelihood of a Trump victory significantly increases or if Trump’s rhetoric triggers aggressive responses from China or the European Union. A sudden downward revision in global growth expectations would likely result in equity price declines and UST yield reductions, added pressure on EM and other spread sectors, a decrease in oil prices, and a strengthening of the US dollar versus the Chinese yuan.

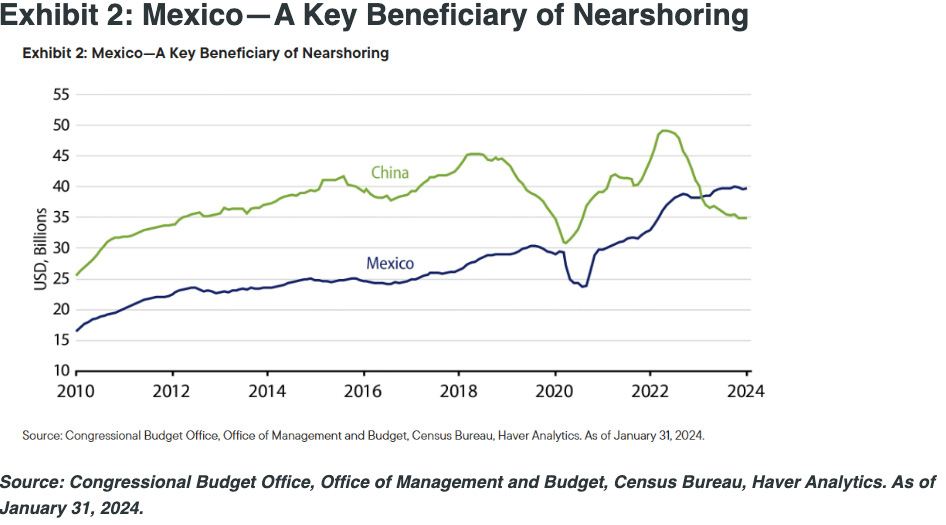

Abad says: “For now, we refrain from making definitive conclusions regarding the outcome of the US presidential election. However, a couple of observations suggest that markets may not experience the same degree of volatility as seen during the 2018-2019 episode. First, Trump’s trade policy is now well-established, so it lacks the element of surprise that characterized his previous impromptu announcements on social media. And second, following the experience of a Trump presidency, governments and corporations worldwide have implemented contingency plans to manage global trade and supply-chain disruptions through nearshoring strategies.8”

So would a trade war lead to higher inflation and potentially higher interest rates?

Abad notes: “That’s a common assumption among many investors. However, it’s also a common misconception based on what seems like an obvious connection—tariffs raise prices, and higher prices lead to higher inflation. In the past, we argued that while tariffs may initially increase prices, as some of the tariff costs are absorbed by importers’ margins, the price hike is typically a one-time occurrence that dissipates relatively quickly. In contrast, when investors discuss “inflation,” they usually refer to a continuous process with prices expected to rise month after month and year after year.

“We believe the more critical point to emphasise is the adverse impact tariffs could have on aggregate demand and long-term growth. For instance, the enactment of the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariffs in the US coincided with the onset of the Great Depression and the most severe deflationary period of the last century.

“The short-term inflationary effects of a single tariff imposition can transform into a deflationary spiral when trade conflicts escalate and trigger a series of retaliatory measures. With this in mind, it’s reasonable to anticipate that the economic and financial impacts of Trump’s more confrontational trade measures will ultimately exert downward pressure on DM government bond yields.

“At present, our focus is squarely on monitoring key economic data trends and the factors influencing credit market fundamentals. While our baseline scenario suggests a moderation in global growth and inflation, coupled with potential policy easing by major central banks—all of which bode well for short and intermediate segments of investment-grade and high-quality high-yield credit, as well as EM local-currency-denominated government debt and USD-denominated frontier markets—we are mindful that market risks are multifaceted.

“For instance, global credit markets are currently enjoying robust investor demand owing to attractive income and return prospects compared to recent history. However, the escalation of trade war concerns could drastically reshape global growth expectations and market sentiment, triggering significant valuation adjustments across various spread sectors.

“This underscores the need to maintain well-diversified portfolios, with USTs serving as the primary hedge against downside growth risks, particularly if exacerbated by a global trade war.”

Endnotes:

- Source: “How scared is China of Donald Trump’s return?” The Economist, February 20, 2024.

- Source: Stein, J. “Donald Trump is preparing for a massive new trade war with China,” Washington Post, January 27, 2024.

- Ibid.

- Source: “Trump floats ‘more than’ 60% tariffs on Chinese imports,” CNBC, February 4, 2024. Note: As an example, tariffs on Chinese mobile phones would jump from 0% to 35% and from 0% to 70% for Chinese toys, according to Oxford Economics.

- According to Moody’s Analytics, “the trade war with China cost an estimated 0.3 percentage point in US real GDP and almost 300,000 jobs. The hit to the global economy was more substantial, particularly to more open economies in Southeast Asia and in Europe.” Source: “Trade War Chicken: The Tariffs and the Damage Done,” September 2019. According to Oxford Economics, an escalation of US tariffs would likely trigger retaliatory measures from China, causing additional US jobs and output losses, pushing the peak impact to 801,000 net job losses by 2025.” Source: “The Impact of China PNTR repeal and increased tariffs on US Economy and American Jobs,” November 2023.

- Source: Amiti, M. Kong, S. and D. Weinstein, “The Investment Cost of the U.S.-China Trade War,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Liberty Street Economics, May 28, 2020.

- Sources: “China’s Yuan Drops to a Decade-Low, 7 Per Dollar Now in Sight,” Bloomberg, October 30, 2018. “Currencies at 2019 lows on trade jitters, stock slides,” CNBC, May 17, 2019.

- Sources: “A potential Trump win has companies already planning for Chinese tariffs and a new trade war,” CNBC, March 11, 2024. “How Washington is bracing for Trump’s next trade war,” Politico, February 6, 2024