Jay Sivapalan, Head of Australian Fixed Interest for Janus Henderson Investors, discusses the very different investment landscape we find ourselves in after the pandemic and how fixed interest investors can navigate the very different path ahead.

Key takeaways:

- Dominant macro themes, including the restructuring of global trade, national security and geopolitical risk, and the energy transition will shape markets.

- Inflation is cyclical and structural and both are in play today.

- Investors will need to balance short-term and longer-term structural trends and actively navigate the cycle to preserve capital and extract return opportunities.

Following the pandemic recovery, markets are burdened with the task of ‘normalising’ from unprecedented levels of monetary and fiscal support. Finding natural market pricing after the COVID-driven distortions of the past two years is unlikely to be an orderly process, particularly given the very different world we find ourselves in today. Dominant macroeconomic themes must be incorporated into investment decisions going forward, rather than assuming a return to pre-pandemic norms. In this article, we discuss the key themes to watch, the risks and opportunities within fixed interest and how investors can navigate the path ahead.

The ‘big picture’ themes

Trading blocs or de-globalisation?

Given the stable state of global trade over the past four decades, this enabled investors to make certain assumptions when pricing assets. In recent years, while events such as Brexit and the US/China trade wars have led to the growing view that markets are de-globalising, our view is that rather than the start of de-globalisation, we were in fact witnessing the re-arrangement of global trade into like-minded trading, security and defence blocs.

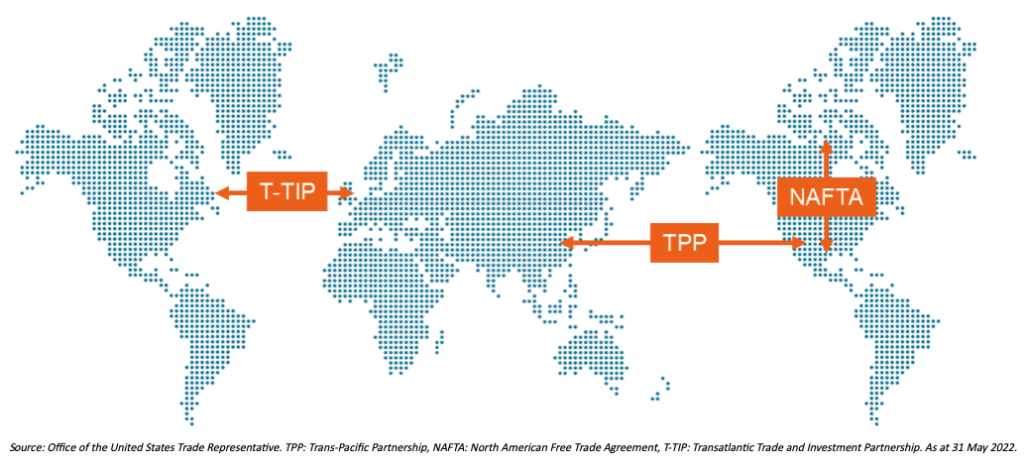

Chart 1: Free trade agreements

We see two main groups emerging – democratic, capitalist developed nations along with their aligned developing partner nations, and socialist, communist nations with their developing nation peers. Recent geo-political events, such as the West’s condemnation and sanctions due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have provided a glimpse into these alliances in action.

While we see the global economy heading towards these trading blocks, where raw materials or efficiency is too hard or too costly to substitute, we expect trade to continue across economic block lines thereby limiting the economic impact.

Nationalisation or national security?

Again, given the relative peace and stability experience over the past 70 years, markets have been able to make certain assumptions when pricing assets. Today, assertive action from Russia and China aimed at challenging the US’ status as ultimate super-power are becoming more commonplace.

The pandemic laid bare the vulnerabilities of nations to supply dislocations and weaknesses in their manufacturing sectors (domestic mask manufacturing are a case in point) when cut-off from the rest of the world.

While there has been suggestion by market participants that a trend of nationalisation has emerged, this suggests countries are pursuing a closed economic model. We believe that rather than nationalism, economies are more likely to pursue national resilience and security, while remaining open to trade with chosen trading partners. Resilience means investment in defence, cyber-security, health systems and advanced manufacturing, making countries more self-sufficient in a period of growing geo-political instability.

Energy transition: A cost burden or benefit?

The transition to renewable energy and targeting net zero emissions is likely to give rise to both opportunities and threats for investors. The risks range from physical asset risk, stranded asset risk and revenue loss risks, while the potential opportunities resulting from this multi-trillion dollar, long-term investment thematic are broad and include initiatives related to green hydrogen, solar, wind, hydro power generation, battery storage and the infrastructure required to enable the electrification of the economy.

Beyond emissions targets, the newly-elected Labor Government has committed to a target of 80% renewable energy in the electricity mix by 2030. A lofty goal, the government aims to achieve this through community batteries, low-cost solar banks, the building of new electricity transmission infrastructure and improvements in existing industry’s energy efficiency.

With large scale capital investment, Australia also has the potential to become a leader in renewable energy generation. Being endowed with abundant space, along with sun, wind and river systems, Australia’s renewable energy needs could be catered for, and the export of energy via undersea cables to neighbouring countries could be a viable industry and economic growth engine if the opportunity is seized correctly.

Navigating inflation

Cyclical inflation

A pandemic downturn ‘like no other’, meant that a recovery ‘like no other’ would be experienced as economies re-emerged from the economic nadir. Supply side inflation has been exacerbated by a global economy that froze during the pandemic, attempting to get back to full speed while simultaneously dealing with soaring energy prices and supply dislocations across items such as semi-conductors, shipping containers, palettes and building materials.

Demand side inflation has varied considerably across, with countries such as the US which is exhibiting pass through from producer prices to consumer prices and wages inflation. In Australia there is mounting evidence of the coming wages inflation led by consumer prices, albeit lower than some other economies.

Exceptionally strong economic growth typically comes with some growing pains. In our assessment, inflation is likely to be higher than most expect in the near-term, is likely to be sticky and eventually moderating at a higher level. Nevertheless, in our view, economies are in the eye of the storm from a cyclical perspective at present, but this should subside over time.

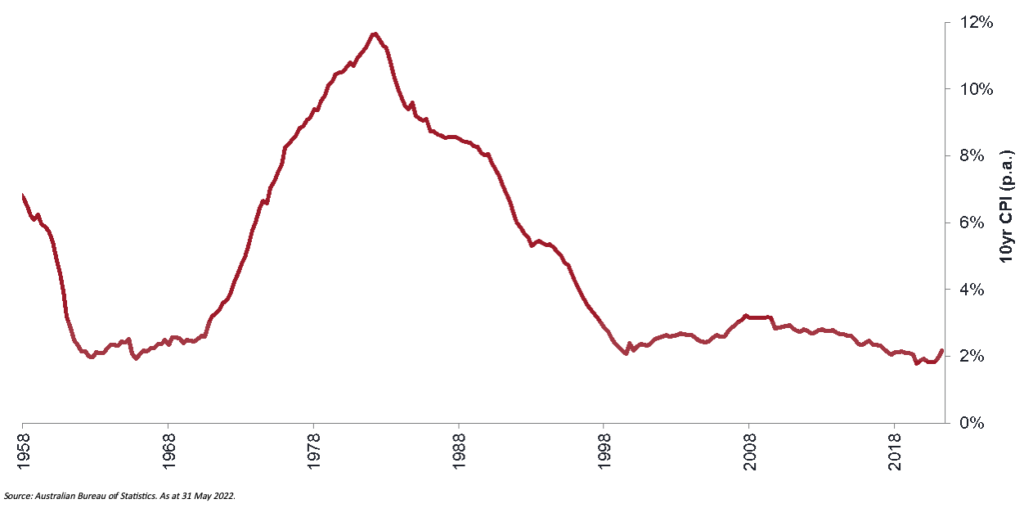

Chart 2: 10-year headline inflation

Long-term inflation expectations now priced inside the RBA lower band

Structural inflation

Many of the prior considerations for structural inflation, including excess savings, an ageing population, high debt levels and technological disruption have not disappeared.

Markets previously ran with the theme of ‘Japanification’ and deflation, which sat at odds with our assessment despite being in agreement about many of the underlying currents. The flaw in that thought process was to not properly distinguish between an economy like Japan with other countries like Australia where aspects such as net migration and rising female participation more than offsets the ageing population issue in terms of supply side estimates of GDP growth.

It is important to take a balanced view about the future structural inflation and not to assume it is a given over the long-term.

Managing portfolios through inflation

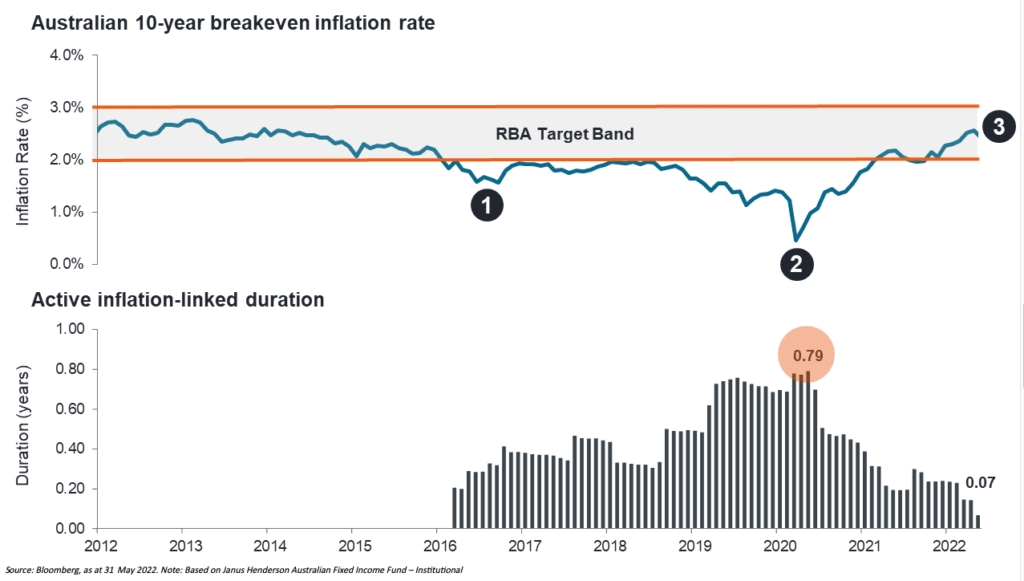

For investors, the more relevant consideration is whether the pricing of inflation protection by the market, implied by breakeven rates, are cheap, reasonable or expensive. In our view, investors in 2020 were being paid to take inflation protection, in 2022 the cost of inflation protection is relatively cheap and we expect this will become expensive in 2022. Taking active views on inflation will offer opportunities to add value in portfolios.

Chart 3: Inflation linked exposure – Janus Henderson Australian Fixed Interest Fund – Institutional

Bonds: Risks and opportunities today

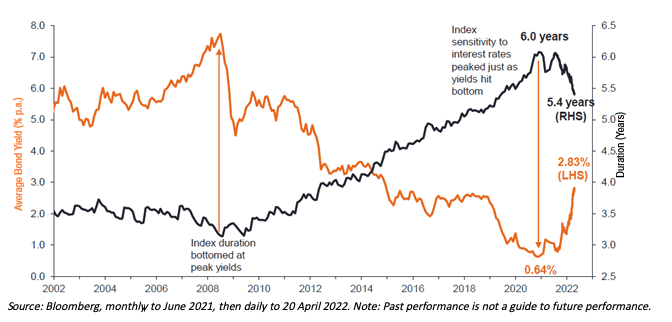

Bond yields, as represented by longer-term US treasury yields over the past 100 years have averaged somewhere in the 4-6% range (US Federal Reserve. As at 31 May 2022). Over the past 40 years, bond yields have been on a one-way journey, declining from over 10%, to a low of close to zero (and beyond in some markets). Over the past four decades, fixed interest has delivered returns well in excess of the coupon (income), with capital gains boosting returns. In short, a lot of returns were brought forward as yields reached extreme lows during the pandemic.

The key questions for investors are what ‘normal’ looks like for bond yields, how much they have already re-priced and how quickly they will get back to normal.

In our view, the first three of the past four decades was bond yields normalising (falling) following a period of extraordinarily high inflation, back towards the 100-year average. However, the past decade has seen excessive use of unconventional monetary policy by central banks and in our view, these actions pushed yields well below ‘normal’.

Most recently, we have witnessed a sharp reversal of the extreme valuations of bond markets globally. Combined with the fact that the duration of bond markets was elevated from longer tenor supply, this provided the perfect storm, with double digit negative returns from the asset class.

Chart 4: Bond yields lift as cycle moves to tightening Index duration moves in directions opposing investor preferences

While a normalisation of monetary policy was an inevitable outcome of the post-pandemic economic recovery, markets have taken the normalisation theme to extreme levels in the near-term, pricing in 350bps of cash rate hikes over the next 18 months in April.

Although over the longer-term some of the structural inflationary forces could drive investors to demand higher term premia, over the nearer-term a lot is priced in already. This has come at a time of heightened inflation and a general ‘risk-off’ phase in risk assets.

Bond investing is rarely about the direction of cash rates, but rather about what’s already priced in relative to how fundamentals may eventuate.

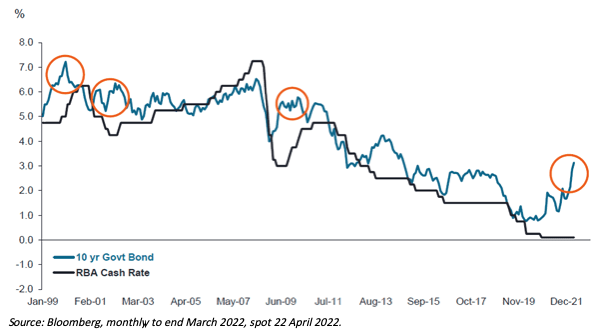

Chart 5: Australian interest rates and 10-year government bond yields

Markets are typically fully-priced before the first hike

With markets having priced in 350bps of cash rate hikes in April by the RBA over the next 18 months, coupled with high levels of household debt, elevated house prices and a housing construction sector reliant on the healthy the state of household wealth, we expect a dramatic slowdown in the Australian economy. We expect this not to be driven by defaults and financial stability concerns, but rather significantly lower consumption and economic growth. While this magnitude of cash rate tightening is possible over the medium-term, especially if we are in the early stages of a shifting landscape in inflation requiring higher neutral cash rates in the long-run, it is unlikely to be delivered over such a short timeframe as priced by markets.

We assess that the RBA will normalise policy swiftly in the initial stages, but take feedback from the economy and be more measured and drawn-out in the latter stages of this tightening cycle. Conventional thinking would favour short duration or defensive strategies, yet amongst the volatility lies some great targeted investment opportunities by taking both interest rate and spread risk within specific parts of the yield curve.

An opportunity exists for investors to effectively ‘lock in’ the elevated yields in markets today that are unlikely to be delivered by the RBA over the next 12-24 months.

Looking forward

There is still a journey ahead in the pandemic economic recovery. Longer-term structural changes have been brought to the fore by a restructure of global trade, a desire for national security and resilience driven by geopolitical risks, along with growing support for the energy transition as the world targets a low-carbon future.

For bond markets, key features in the journey ahead relate to pricing in the normalisation of policy and determining the neutral yield levels over the longer-term to properly compensate investors for inflation and ultimately term risk premia.

This journey will be neither smooth nor easily predictable and active management and careful analysis will be vital in navigating the risks and identifying the many opportunities that will emerge.