This article on the UK government’s green gilt was written by Anastasia Petraki, Head of Policy Research at Schroders, and Saida Eggersted, Head of Sustainable Credit at Schroders. The original article can been found here and has been republished with permission.

With the COP26 climate summit in November fast approaching, all eyes are on the green ambitions of its host – the UK.

The UK government has set its course toward a green and sustainable future economy. In 2019, it became the first major country to pass legislation committing to achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

A succession of additional announcements followed, with the UK setting out its plan for a “Green Industrial Revolution”, a 10-point plan comprising £12 billion of investment to support 250,000 skilled green jobs. Headline objectives include quadrupling offshore wind capacity, promoting electric vehicle production and charging infrastructure, and supporting research for zero-emission planes and ships.

ALSO READ: 3 Green Bond Funds for Climate Change Investors

The UK leads in its ambition to reduce its carbon emissions by at least 68% by 2030 (from 1990 levels). But, unlike neighbouring countries such as Germany, France or even Italy, that have already tested the green bond market, the UK government waited for a gentle push from impact investors to come up with such a framework.

The story is similar for corporate bonds. While UK investors, including pension funds, have been eager to deepen the green credentials of their portfolios, the supply of sterling denominated green bonds has largely lagged the rapid growth in green bonds issued in other currencies generally, and the euro specifically.

The UK’s position may soon change, however, with the first ever UK green government bond (green gilt) issue expected in September 2021. In this article, we look under the bonnet of the green gilt framework that the UK government has just unveiled and we highlight the aspects that we think are important for success.

How does the green gilt fit into the UK’s plans for sustainable finance?

The green gilt is part of a much broader sustainable finance agenda. The purpose of this agenda is to ensure private funding to realise all the investments needed for the UK’s transition to net zero. The 2021 Budget outlined the main components:

- £15 billion in green gilts for the current financial year, to create a “green curve”

- A green retail savings product though NS&I, the UK’s state-owned savings bank, called the “Green Savings Bond”

- Amending the Bank of England’s (BoE) remit to target environmentally sustainable growth, to which the BoE has already reacted with a consultation on how to make its Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme greener

- The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations becoming mandatory for companies and the financial services sector in waves. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is currently consulting on extending the TCFD requirements to all listed companies as well as asset managers, life insurers, and FCA-regulated pension providers.

More action is in the works, such as plans for the UK regulator to develop a label for sustainable retail investments.

The UK is also working towards a Green Taxonomy, which will serve as a cornerstone for the sustainable finance industry. This taxonomy will provide the framework for classifying which investments can be defined as environmentally sustainable. It will draw from the EU Taxonomy and, in due course, is going to become a reference point for green bonds issued by both corporates and the government in the UK.

What does the green gilt framework look like?

The framework covers not only the green gilt but also the Green Savings Bond as well as any future (still unspecified) green finance instrument. The proceeds from all three are collectively referred to as ”Green Financing”.

The Treasury has confirmed that it “intends, where possible, to adhere to best practices in the market” and will follow the Green Bond Principles of the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA). Although these are voluntary, they are often viewed as the de facto standard for green bonds. In alignment with them, the Green Financing Framework has four key aspects:

1. Use of proceeds

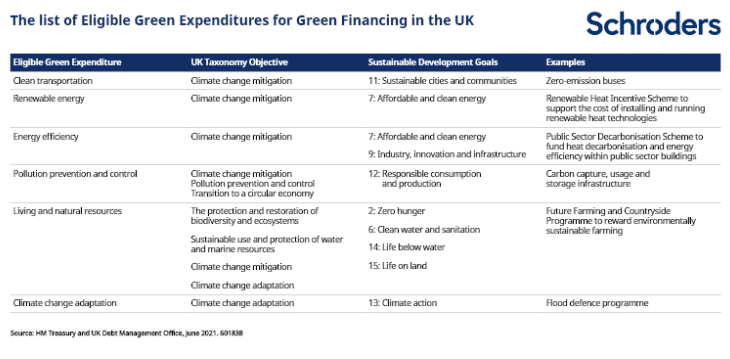

The UK has chosen to align the use of proceeds from its Eligible Green Expenditures to target nine Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This reflects the wider scope it intends to cover in its green financing. Starting from climate change mitigation and pollution prevention, it also includes the transition to a “circular economy”, where resources are reused with a view to minimising waste, and the protection of biodiversity and marine resources. This is what we, at Schroders, had hoped to see.

Importantly, there is a list of activities that should not be on the receiving end of the UK’s Green Financing such as vehicles powered through fossil fuel combustion and ethanol, fossil fuel exploitation and exploration more generally, large-scale hydroelectric energy due to potential risk to natural habitats, weapons, tobacco, gaming, and palm oil industries, direct manufacture of alcoholic beverages etc.

Any nuclear energy-related expenditures are also excluded although the framework states that for the UK government “nuclear power is, and will continue to be, a key part of the UK’s low-carbon energy mix”.

2. Process for project evaluation and selection

While it is expected from a corporate issuer to demonstrate that a green bond is aligned with the wider objectives of the issuer or market-based taxonomies, in the case of a sovereign like the UK, investors value the ongoing participation of diverse experts at national and local levels. This is to ensure that the green issuance is both effective and impactful.

The UK Treasury will put together an Inter-departmental Green Bond Board (IDGBB), which it will chair and which will also include representatives from:

- the UK Debt Management Office (DMO)

- the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS)

- the Department for Transport (DfT)

- the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra)

- the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO)

- NS&I

The IDGBB will oversee the evaluation and selection of Eligible Green Expenditures, the allocation and management of proceeds, and advise the Treasury on the overall implementation of the framework. Nevertheless, the Treasury will have the “final decision-making on all of these matters”.

A Stakeholder Discussion Forum (SDF) will also be set up by the Government. Its main purpose is to advise the IDGBB on technical and other aspects and to give an independent view.

Quite probably, the UK government will receive enough questions around the framework from both traditional and sustainable bond investors during the roadshow of its green gilt. This too can serve as feedback for the IDGBB and help inform on various aspects of the overall framework.

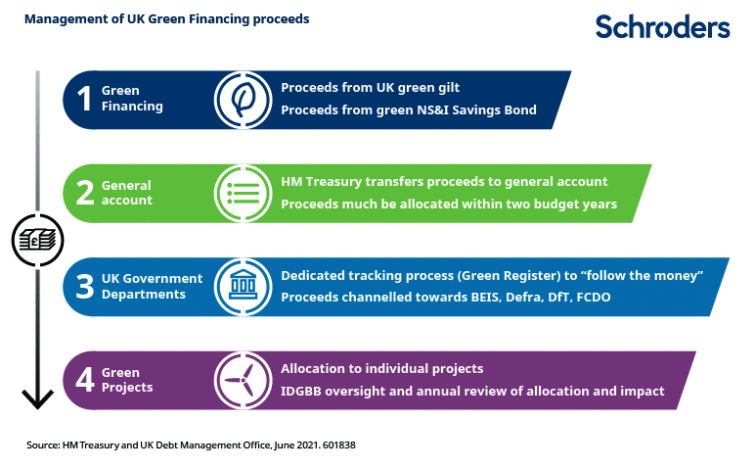

3. Management of proceeds

The proceeds from Green Financing (which includes both the green gilt and the green NS&I product) will be transferred to a general account, from where they will be tracked via a dedicated tracking process in the “Green Register”. The creation of a Green Register reflects the ICMA standard that green bond net proceeds be kept in a sub-account.

The UK framework also states that proceeds will be allocated within two budget years to green projects. This is welcome as it helps to reduce uncertainty about unrealistic plans and can, hopefully, drive better prioritisation and coordination.

Moreover, aligned with best practice, an authorised independent entity will verify the allocation and impact reporting (more on this below) as well as the compliance of expenditures and the management of both allocated and unallocated proceeds.

4. Reporting

We very much welcome the reporting aspects of the UK framework.

Namely, the UK government has confirmed that there will be an annual allocation report and a biennial impact report, as a minimum. These will draw from information by the individual government departments that have allocated proceeds into specific projects. The IDGBB will consolidate the information into the allocation and impact reports, both of which will be subject to an external audit before being made available publicly on the government’s website.

The allocation report will focus on how the proceeds have been spent, how much remains unallocated and whether any proceeds have been allocated to refinancing existing Eligible Green Expenditures.

The impact report will largely contain metrics quantifying environmental impact, such as greenhouse gas emissions reduced or avoided, reduction of air pollutants, number of properties protected by floods, annual energy savings, and number of native species benefiting from specific projects (where relevant). The report will also contain social impact indicators such as number of jobs created, number of households benefiting from an improvement, or number of small and medium sized enterprises that have received specific support.

Green gilt needed to put the UK on the map

The green gilt is needed.

Schroders has backed proposals from the Green Finance Institute and the Impact Investing Institute for the government to issue a Green+ gilt as a clear commitment to the environment, investors and future generations. We welcome the fact that the framework includes key points from this engagement.

Green bonds are no magic solution and, on their own, no guarantee that any economy will get to net zero. For some, they are even pose the risk of “greenwashing”. Transparency and reporting around the use of proceeds can help to manage this risk. But, even so, the reality is that the green bond market is blooming and this growth is happening elsewhere.

According to data from the Climate Bonds Initiative, the cumulative issuance of government and corporate green bonds surpassed the $1 trillion mark for the first time in 2020. The bad news for the UK’s stand in the international sustainable finance arena is that sterling denominated bonds accounted for less than 2% of that.

For Schroders, a key benefit of the green gilt is its potential to put the UK on the green bond map and we see this as the first step for the UK to get up to speed with other countries. It could also spur UK companies to follow suit and issue green bonds in the sterling market, as has been the case in other countries.

This would be very much welcome as the UK green corporate bond market remains relatively small, despite many UK companies having good green and sustainability initiatives. At the same time, the Climate Change Committee has highlighted that some sectors, such as surface transport, electricity supply, and manufacturing and construction, would still need to achieve significant decarbonization to reach net zero. The sooner companies in those sectors can get guiding policies and funding to support their transition, the better.

Another benefit of having a green gilt is that it could set the tone for the interaction between investors and the sovereign. This interaction could also help identify the best way for the public and private sectors to support each other in their journey towards carbon neutrality.

The three Cs in the green gilt framework that are important to us

In our view, issuance of green gilts needs to encompass the three Cs: coordination, comprehensiveness and credibility.

- Coordination. Given the scope of the UK’s plans, we are encouraged to see involvement from a range of government departments. The Treasury will clearly have a central role, but the green and social projects will cover a whole range of areas: transport, work and pensions, housing, health and social care, to name a few. Ideally, independent agencies would be involved at the IDBGG level rather than the stakeholder forum (where we would expect them to be included). We anticipate that the regular reviews can indicate whether the need for this arises and we are encouraged by the proposals for granular reporting.

- Comprehensiveness. The main intention of our engagement on the Green+ bond was that use of proceeds should go beyond green objectives to incorporate social impact objectives too. Ultimately, green investment should aim to create a more sustainable economy that underpins better living standards, opportunities and prospects for people and communities. The creation of ‘green collar’ jobs is key in the government’s plans and vital, considering the potentially lasting damage of the pandemic. We welcome the inclusion of social impact metrics but note that these focus entirely on number of jobs, households and businesses and say nothing about the regional footprint. We believe that the benefits, such as new green jobs, should be created across the country. The proceeds of the green gilt would then have a footprint that spreads over all regions in the UK so as to address the long-term regional inequalities in the country and contribute to the levelling up agenda.

- Credibility. Transparency and disclosure through reporting and a well articulated governance framework are key here. As a potential investor in the green gilt, we will need to verify through engagement and analysis that the plans are realistic, impactful and properly budgeted. This means that we make sure the projects are worthwhile and that risks such as social and biodiversity impact are factored in. As a first step, we welcome that, for a sovereign, the intended impact report shows granularity and is designed to deliver transparency on both environmental and social impact.

Beyond that, we welcome the fact that the framework makes the connection between climate change and protecting the natural environment as well as that it makes references to the government’s commitment to “delivering a nature positive future” and to following a “path to net zero and nature positive”.

It is encouraging that there is a specific category of green financing dedicated to natural capital and biodiversity (“Living and natural resources”). Having said that, we look forward to understanding better the intended allocation of green proceeds, as we note that the Carbon Trust pre-issuance impact report estimates that over half of the eligible spend will be focused on transportation and much less on natural resources.

The green gilt could be a real opportunity for the country to create a virtuous circle by helping different sectors to be more sustainable, encouraging further green bond issuance by corporates and raising public awareness. We look forward to seeing the first green gilt making its debut on the global green bond market stage.