-

A major macro regime transition for 2025

-

Risks to US market rates are no longer skewed to the downside

-

Rosy vs. gloomy, a different growth picture when you look at the US vs. Europe

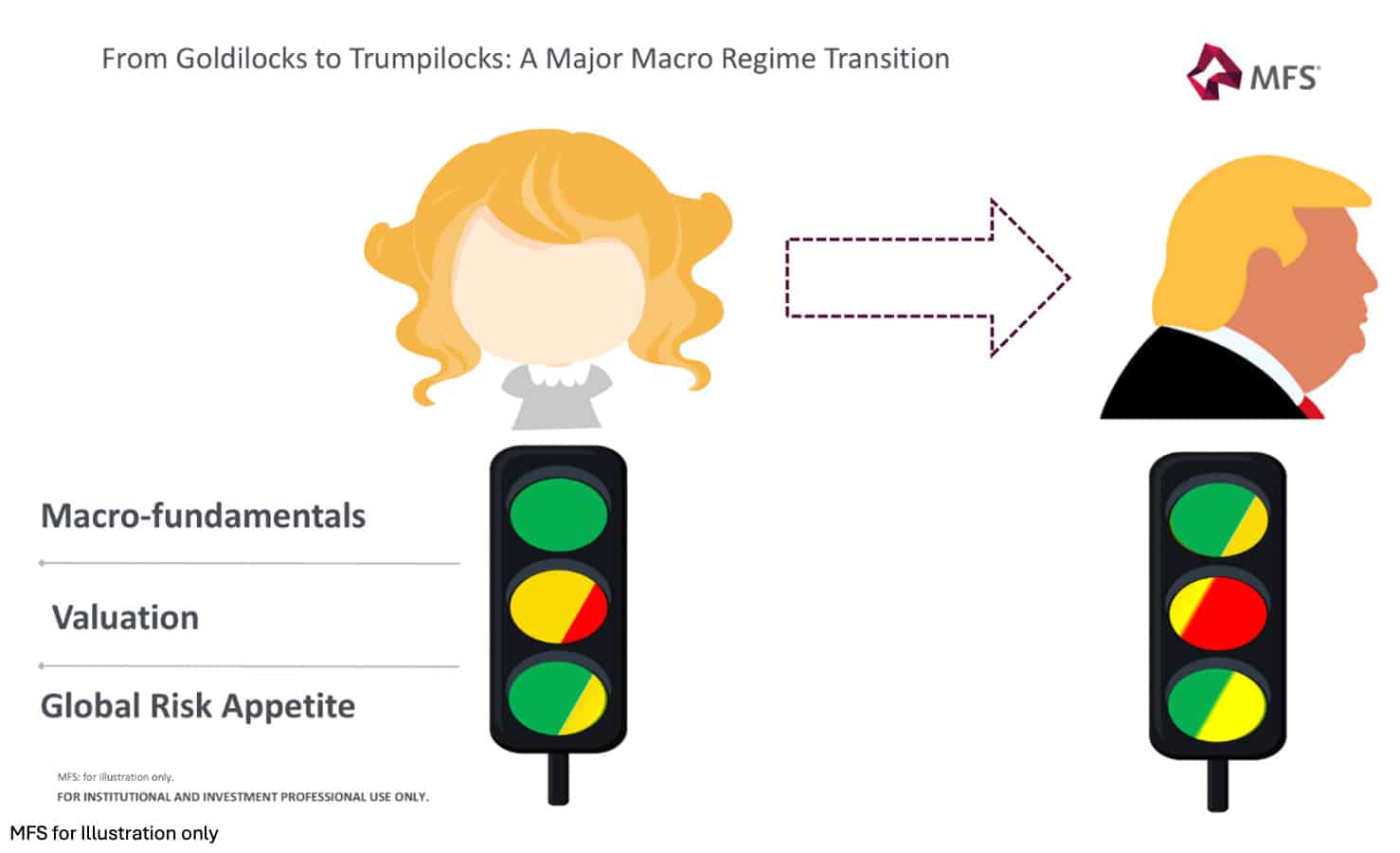

From Goldilocks to Trumpilocks. You remember Goldilocks, that time when the market backdrop looked quasi-perfect, both for fixed income and equities? Well, it is gone. We are moving to a new macro regime, which I have labelled Trumpilocks. To be clear, it is not all about Trump 2.0 and its impact, although that bit plays a big role. Besides Trump 2.0, the Fed has hit the breaks, as a result of stronger-than expected economic activity and slower progress towards disinflation, and that is also a major consideration. Under Trumpilocks, it is much harder to hold a high conviction call on being long duration, mainly because the inflation outlook is less supportive. There are also a number of risks that may cloud the risk appetite backdrop, ranging from a potential trade war to geopolitics. Risky assets may continue to do well, but there are nonetheless concerns over the market valuation landscape and the impact of risks discussed above. Meanwhile on the fixed income front, we probably have lost the impetus of policy rate cuts as a key driver of fixed income expected returns, especially in the US. That is by the way another key feature of Trumpilocks: the great bifurcation. The world has become unsynchronized, including for monetary policy and the macro outlook. In particular, the Eurozone remains in Goldilocks mode from a fixed income standpoint, given the need for the ECB to go ahead with its policy easing. This actually represents a potentially fertile environment for a global active asset manager, as there should be plenty of relative value opportunities and dislocations in the period ahead. At the same time, we anticipate that macro volatility will remain elevated. Finally, from an equity-bond correlation standpoint, under Trumpilocks, fixed income should gradually regain its status as a portfolio diversifier, with the correlation anticipated to normalize lower.

The risk to rates is no longer substantially skewed to the downside. It is fair to say that the tactical case for being long duration is not as strong as it used to be just a few months ago. In fact, the majority of MFS’ fixed income portfolio managers have revised their market rate projections upwards. Additionally, the quant investment team rate forecast —which is based on curve slope and real yield modelling— takes a neutral view on market rates, supporting that notion that caution is probably needed on duration positioning in the period ahead. This week is going to be a heavy one on the US politics and policy fronts, and therefore a near-term spike in rate volatility appears likely. Overall, it seems that carry is going to play out as the primary driver of fixed income expected returns in the period ahead. Spread compression, in contrast, is unlikely to be helping in a major way given where spreads are. Finally, the earlier “cut and carry” Market Insights theme has now been overtaken by the recent market developments, with the tactical case for duration becoming a bit more challenged.

Also read: Risky Assets Do Not Like Strong Macro Data

This is not the end of the business cycle. In the US at least. At this point, recession risks are as low as they have been since May 2022, at least according to the Market Insights’ business cycle indicator—which aggregates selected leading indicators for the US. In other words, the US economy is still going strong, and behaves as if we are still in mid-cycle. If anything, the risk at this juncture is that the US economy may tip into overheating, which would likely undermine global risk appetite. Both Fed GDP nowcast projections (from the Atlanta and New York Fed) point to a 3% growth estimate for Q4-2024, which is remarkably healthy. If that number were to materialize, it would be the third quarter in a row with GDP growth exceeding 3%. Impressive but this begs the fundamental question whether the US has shifted to a structurally higher growth trajectory. If it does, this is great news for risky and growth assets. This is because by now, one should have expected some sort of slowdown, but no such thing so far. In contrast, the growth outlook for the Eurozone is a lot gloomier, and the near-term dynamics is the exact opposite of what we are observing in the US. The risks in Europe are skewed to the downside, with most leading indicators going South. This by the way reinforces the case for monetary policy divergence, with the ECB likely to remain aggressive throughout the year. From a fixed income perspective, there is divergence between the attractiveness of the US market and that of the Eurozone, with the latter being more compelling as a place to be.